Chapter 3

Chemistry and Life

3.1 The Building Blocks of Molecules

Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

-

Describe matter and elements

-

Describe the interrelationship between protons, neutrons, and

-

electrons, and the ways in which electrons can be donated or shared between atoms

At its most fundamental level, life is made up of matter. Matter occupies space and has mass. All matter is composed of elements, substances that cannot be broken down or transformed chemically into other substances. Each element is made of atoms, each with a constant number of protons and unique properties. A total of 118 elements have been defined; however, only 92 occur naturally, and fewer than 30 are found in living cells. The remaining 26 elements are unstable and, therefore, do not exist for very long or are theoretical and have yet to be detected.

Each element is designated by its chemical symbol (such as H, N, O, C, and Na), and possesses unique properties. These unique properties allow elements to combine and to bond with each other in specific ways.

Atoms

An atom is the smallest component of an element that retains all of the chemical properties of that element. For example, one hydrogen atom has all of the properties of the element hydrogen, such as it exists as a gas at room temperature, and it bonds with oxygen to create a water molecule. Hydrogen atoms cannot be broken down into anything smaller while still retaining the properties of hydrogen. If a hydrogen atom were broken down into subatomic particles (i.e. protons, neutrons, and electrons), it would no longer have the properties of hydrogen.

At the most basic level, all organisms are made of a combination of elements. They contain atoms that combine together to form molecules. In multicellular organisms, such as animals, molecules can interact to form cells that combine to form tissues, which make up organs. These combinations continue until entire multicellular organisms are formed.

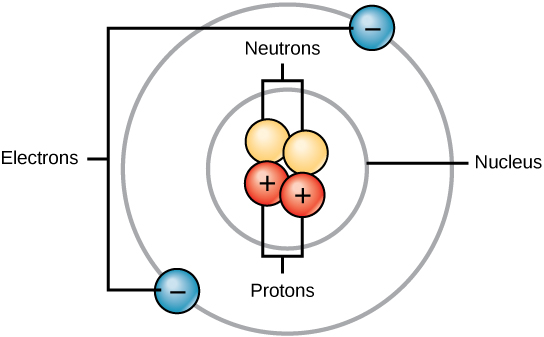

All atoms contain protons, electrons, and neutrons (Figure 3.2). The only exception is hydrogen (H), which is made of one proton and one electron. A proton is a positively charged particle that resides in the nucleus (the core of the atom) of an atom and has a mass of 1 and a charge of +1. An electron is a negatively charged particle that travels in the space around the nucleus. In other words, it resides outside of the nucleus. It has a negligible mass (i.e. considered to be zero compared to protons and neutrons) and has a charge of –1.

Neutrons, like protons, reside in the nucleus of an atom. They have a mass of 1 and no charge. The positive (protons) and negative (electrons) charges balance each other in a neutral atom, which has a net zero charge.

Because protons and neutrons each have a mass of 1, the mass of an atom is equal to the combined number of protons and neutrons of that atom. The number of electrons does not factor into the overall mass, because their mass is so small.

As stated earlier, each element has its own unique properties. Each contains a different number of protons and neutrons, giving it its own atomic number and mass number. The atomic number of an element is equal to the number of protons that element contains. The mass number, or atomic mass, is the number of protons plus the number of neutrons of that element. Therefore, it is possible to determine the number of neutrons by subtracting the atomic number from the mass number. For example, the element phosphorus (P) has an atomic number of 15 and a mass number of 31. Therefore, an atom of phosphorus has 15 protons, 15 electrons, and 16 neutrons (31-15 = 16).

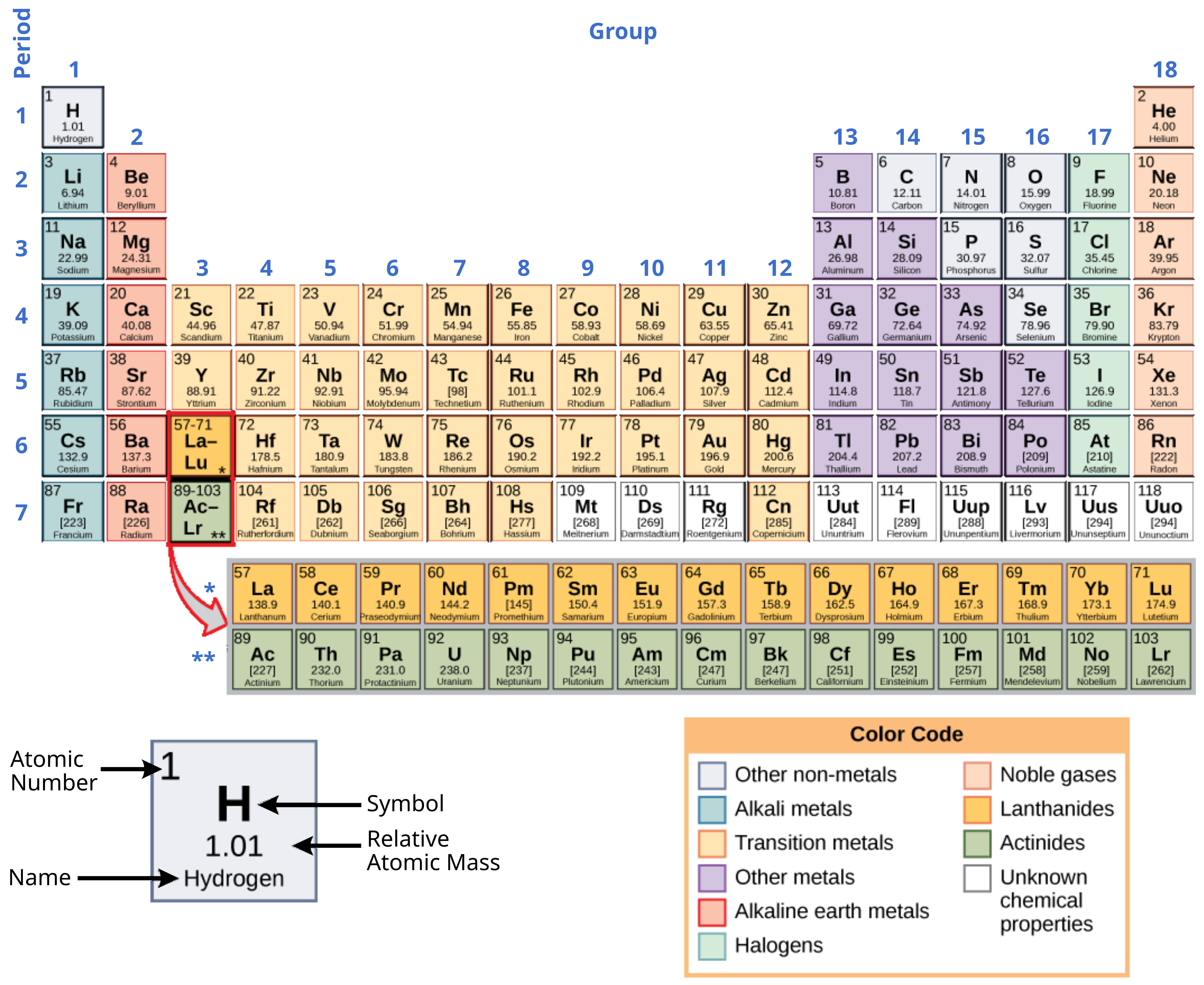

These numbers provide information about the elements and how they will react when combined. Different elements have different melting and boiling points, and are in different states (liquid, solid, or gas) at room temperature. They also combine in different ways. Some form specific types of bonds, whereas others do not. How they combine is based on the number of electrons present. Because of these characteristics, the elements are arranged into the periodic table of elements, a chart of the elements that includes the atomic number and relative atomic mass of each element. The periodic table also provides key information about the properties of elements (Figure 3.3) — often indicated by color-coding. The arrangement of the table also shows how the electrons in each element are organized and provides important details about how atoms will react with each other to form molecules.

Isotopes are different forms of the same element that have the same number of protons, but a different number of neutrons. Some elements, such as carbon, potassium, and uranium, have naturally occurring isotopes. Carbon-12, the most common isotope of carbon, contains six protons and six neutrons. Therefore, it has a mass number of 12 (six protons and six neutrons) and an atomic number of 6 (which makes it carbon). Carbon-14 contains six protons and eight neutrons. Therefore, it has a mass number of 14 (six protons and eight neutrons) and an atomic number of 6, meaning it is still the element carbon. These two alternate forms of carbon are isotopes. Some isotopes are unstable and will lose protons, other subatomic particles, or energy to form more stable elements. These are called radioactive isotopes or radioisotopes.

Evolution in Action

Carbon Dating

Carbon-14 (14C) is a naturally occurring radioisotope that is created in the atmosphere by cosmic rays. This is a continuous process, so more 14C is always being created. As a living organism develops, the relative level of 14C in its body is equal to the concentration of 14C in the atmosphere. When an organism dies, it is no longer ingesting 14C, so the ratio will decline. 14C decays to 14N by a process called beta decay; it gives off energy in this slow process.

After approximately 5,730 years, only one-half of the starting concentration of 14C will have been converted to 14N. The time it takes for half of the original concentration of an isotope to decay to its more stable form is called its half-life. Because the half-life of 14C is long, it is used to age formerly living objects, such as fossils. Using the ratio of the 14C concentration found in an object to the amount of14C detected in the atmosphere, the amount of the isotope that has not yet decayed can be determined. Based on this amount, the age of the fossil can be calculated to about 50,000 years (Figure 3.4). Isotopes with longer half-lives, such as potassium-40 (40K), are used to calculate the ages of older fossils. Through the use of carbon dating, scientists can reconstruct the ecology and biogeography of organisms living within the past 50,000 years.

Concept in Action

To learn more about atoms and isotopes, and how you can tell one isotope from another, visit this site and run the simulation.

Chemical Bonds

How elements interact with one another depends on how their electrons are arranged and how many openings for electrons exist at the outermost region where electrons are present in an atom. Electrons exist at energy levels that form shells around the nucleus. The closest shell can hold up to two electrons. The closest shell to the nucleus is always filled first, before any other shell can be filled. Hydrogen has one electron; therefore, it has only one spot occupied within the lowest shell. Helium has two electrons; therefore, it can completely fill the lowest shell with its two electrons. If you look at the periodic table, you will see that hydrogen and helium are the only two elements in the first row. This is because they only have electrons in their first shell. Hydrogen and helium are the only two elements that have the lowest shell and no other shells.

The second and third energy levels can hold up to eight electrons. The eight electrons are arranged in four pairs and one position in each pair is filled with an electron before any pairs are completed.

Looking at the periodic table again (Figure 3.3), you will notice that there are seven rows. These rows correspond to the number of shells that the elements within that row have. The elements within a particular row have increasing numbers of electrons as the columns proceed from left to right. Although each element has the same number of shells, not all of the shells are completely filled with electrons. If you look at the second row of the periodic table, you will find lithium (Li), beryllium (Be), boron (B), carbon (C), nitrogen (N), oxygen (O), fluorine (F), and neon (Ne). These all have electrons that occupy only the first and second shells. Lithium has only one electron in its outermost shell, beryllium has two electrons, boron has three, and so on, until the entire shell is filled with eight electrons, as is the case with neon.

Not all elements have enough electrons to fill their outermost shells, but an atom is at its most stable when all of the electron positions in the outermost shell are filled. Because of these vacancies in the outermost shells, we see the formation of chemical bonds, or interactions between two or more of the same or different elements that result in the formation of molecules. To achieve greater stability, atoms will tend to completely fill their outer shells and will bond with other elements to accomplish this goal by sharing electrons, accepting electrons from another atom, or donating electrons to another atom. Because the outermost shells of the elements with low atomic numbers (up to calcium, with atomic number 20) can hold eight electrons, this is referred to as the octet rule. An element can donate, accept, or share electrons with other elements to fill its outer shell and satisfy the octet rule. When an atom does not contain equal numbers of protons and electrons, it is called an ion. Because the number of electrons does not equal the number of protons, each ion has a net charge. Positive ions are formed by losing electrons and are called cations. Negative ions are formed by gaining electrons and are called anions.

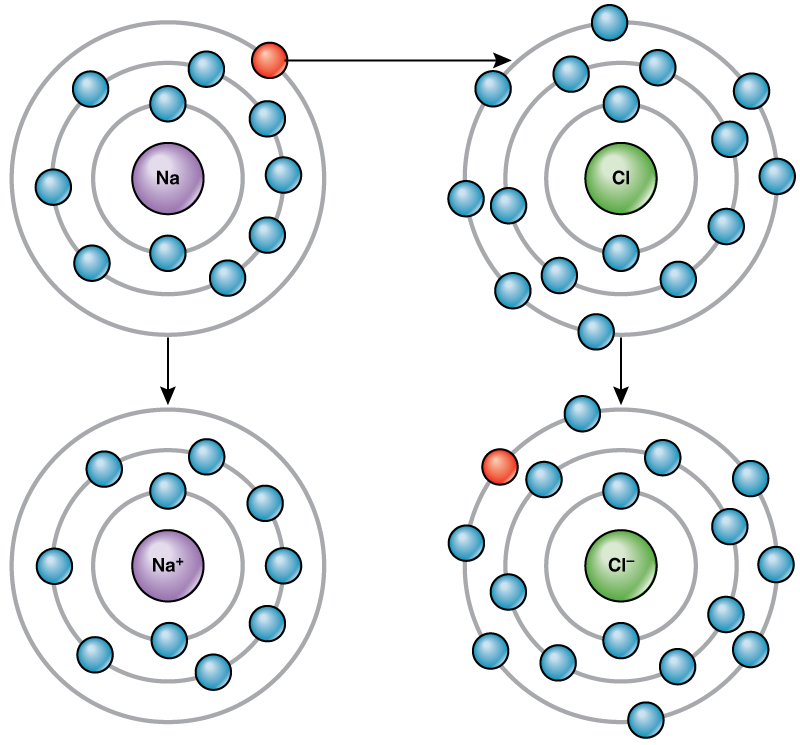

For example, sodium only has one electron in its outermost shell. It takes less energy for sodium to donate that one electron than it does to accept seven more electrons to fill the outer shell. If sodium loses an electron, it now has 11 protons and only 10 electrons, leaving it with an overall charge of +1. It is now called a sodium ion. The chlorine atom has seven electrons in its outer shell. Again, it is more energy-efficient for chlorine to gain one electron than to lose seven.

Therefore, it tends to gain an electron to create an ion with 17 protons and 18 electrons, giving it a net negative (–1) charge. It is now called a chloride ion. This movement of electrons from one element to another is referred to as electron transfer. As Figure 3.5 illustrates, a sodium atom (Na) only has one electron in its outermost shell, whereas a chlorine atom (Cl) has seven electrons in its outermost shell. A sodium atom will donate its one electron to empty its shell, and a chlorine atom will accept that electron to fill its shell, becoming chloride. Both ions now satisfy the octet rule and have complete outermost shells. Because the number of electrons is no longer equal to the number of protons, each is now an ion and has a +1 (sodium) or –1 (chloride) charge.

We will study three types of bonds or interactions: ionic, covalent, and hydrogen bonds.

Ionic Bonds

When an element donates an electron from its outer shell, as in the sodium atom example above, a positive ion is formed. The element accepting the electron is now negatively charged. Because positive and negative charges attract, these ions stay together and form an ionic bond, or a bond between ions. The elements bond together with the electron from one element staying predominantly with the other element. When Na+ and Cl− ions combine to produce NaCl, an electron from a sodium atom stays with the other seven from the chlorine atom, and the sodium and chloride ions attract each other in a lattice of ions with a net zero charge.

Covalent Bonds

Another type of chemical bond between two or more atoms is a covalent bond. These bonds form when an electron is shared between two elements and are the strongest and most common form of chemical bond in living organisms. Covalent bonds form between the elements that make up the biological molecules in our cells. Unlike ionic bonds, covalent bonds do not dissociate (i.e. separate) in water.

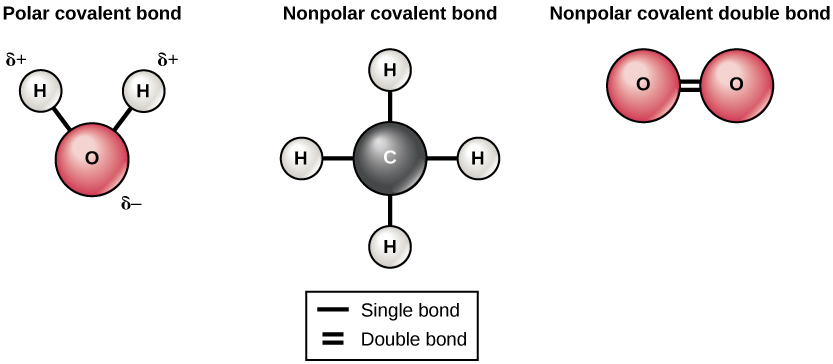

The hydrogen and oxygen atoms that combine to form water molecules are bound together by covalent bonds. The electron from the hydrogen atom divides its time between the outer shell of the hydrogen atom and the incomplete outer shell of the oxygen atom. To completely fill the outer shell of an oxygen atom, two electrons from two hydrogen atoms are needed, hence the subscript “2” in H2O. The electrons are shared between the atoms, dividing their time between them to “fill” the outer shell of each. This sharing is a lower energy state for all of the atoms involved than if they existed without their outer shells filled.

There are two types of covalent bonds: polar and nonpolar. Nonpolar covalent bonds form between two atoms of the same element or between different elements that share the electrons equally. For example, an oxygen atom can bond with another oxygen atom to fill their outer shells. This association is nonpolar because the electrons will be equally distributed between each oxygen atom. Two covalent bonds form between the two oxygen atoms because oxygen requires two shared electrons to fill its outermost shell. Nitrogen atoms will form three covalent bonds (also called triple covalent) between two atoms of nitrogen because each nitrogen atom needs three electrons to fill its outermost shell. Another example of a nonpolar covalent bond is

found in the methane (CH4) molecule. The carbon atom has four electrons in its outermost shell and needs four more to fill it. It gets these four from four hydrogen atoms, each atom providing one. These elements all share the electrons equally, creating four nonpolar covalent bonds (Figure 3.6).

In a polar covalent bond, the electrons shared by the atoms spend more time closer to one nucleus than to the other nucleus. Because of the unequal distribution of electrons between the different nuclei, a slightly positive (δ+) or slightly negative (δ−) charge develops. The covalent bonds between hydrogen and oxygen atoms in water are polar covalent bonds. The shared electrons spend more time near the oxygen nucleus, giving it a small negative charge, than they spend near the hydrogen nuclei, giving these molecules a small positive charge.

Hydrogen Bonds

Ionic and covalent bonds are strong bonds that require considerable energy to break. However, not all bonds between elements are ionic or covalent bonds. Weaker bonds can also form. These are attractions that occur between positive and negative charges that do not require much energy to break. An example of relatively weak bonds that occur frequently is hydrogen bonds. This bond gives rise to the unique properties of water and the unique structures of DNA and proteins.

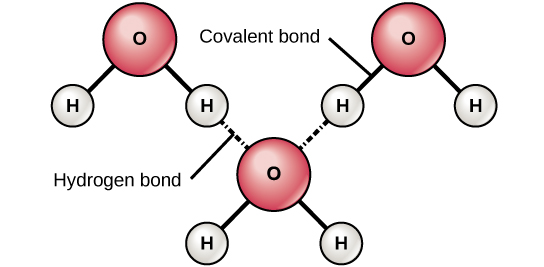

When polar covalent bonds containing a hydrogen atom form, the hydrogen atom in that bond has a slightly positive charge. This is because the shared electron is pulled more strongly toward the other element and away from the hydrogen nucleus. Because the hydrogen atom is slightly positive (δ+), it will be attracted to neighboring negative partial charges (δ−).When this happens, a weak interaction occurs between the δ+ charge of the hydrogen atom of one molecule and the δ− charge of the other molecule. This interaction is called a hydrogen bond. This type of bond is common; for example, the liquid nature of water is caused by the hydrogen bonds between water molecules (Figure 3.7).Hydrogen bonds give water the unique properties that sustain life. If it were not for hydrogen bonding, water would be a gas rather than a liquid at room temperature.

Hydrogen bonds can form between different molecules and they do not always have to include a water molecule. Hydrogen atoms in polar bonds within any molecule can form bonds with other adjacent molecules. For example, hydrogen bonds hold together two long strands of DNA to give the DNA molecule its characteristic double-helix structure. Hydrogen bonds are also responsible for some of the three-dimensional structure of proteins.

Section Summary

Matter is anything that occupies space and has mass. It is made up of atoms of different elements. All of the 92 elements that occur naturally have unique qualities that allow them to combine in various ways to create compounds or molecules. Atoms, which consist of protons, neutrons, and electrons, are the smallest units of an element that retain all of the properties of that element. Electrons can be donated or shared between atoms to create bonds, including ionic, covalent, and hydrogen bonds.

Key Terms

- anion

- a negative ion formed by gaining electrons

- atomic number

- the number of protons in an atom

- cation

- a positive ion formed by losing electrons

- chemical bond

- an interaction between two or more of the same or different elements that results in the formation of molecules

- covalent bond

- a type of strong bond between two or more of the same or different elements; forms when electrons are shared between elements

- electron

- a negatively charged particle that resides outside of the nucleus in the electron orbital; lacks functional mass and has a charge of –1

- electron transfer

- the movement of electrons from one element to another

- element

- one of 118 unique substances that cannot be broken down into smaller substances and retain the characteristic of that substance; each element has a specified number of protons and unique properties

- hydrogen bond

- a weak bond between partially positively charged hydrogen atoms and partially negatively charged elements or molecules

- ion

- an atom or compound that does not contain equal numbers of protons and electrons, and therefore has a net charge

- ionic bond

- a chemical bond that forms between ions of opposite charges

- isotope

- one or more forms of an element that have different numbers of neutrons

- mass number

- the number of protons plus neutrons in an atom

- matter

- anything that has mass and occupies space

- neutron

- a particle with no charge that resides in the nucleus of an atom; has a mass of 1

- nonpolar covalent bond

- a type of covalent bond that forms between atoms when electrons are shared equally between atoms, resulting in no regions with partial charges as in polar covalent bonds

- nucleus

- (chemistry) the dense center of an atom made up of protons and (except in the case of a hydrogen atom) neutrons

- octet rule

- states that the outermost shell of an element with a low atomic number can hold eight electrons

- periodic table of elements

- an organizational chart of elements, indicating the atomic number and mass number of each element; also provides key information about the properties of elements

- polar covalent bond

- a type of covalent bond in which electrons are pulled toward one atom and away from another, resulting in slightly positive (δ+) and slightly negative (δ−) charged regions of the molecule

- proton

- a positively charged particle that resides in the nucleus of an atom; has a mass of 1 and a charge of +1

- radioactive isotope

- an isotope that spontaneously emits particles or energy to form a more stable element

- van der Waals interaction

- a weak attraction or interaction between molecules caused by slightly positively charged or slightly negatively charged atoms