5 Diversity and Accessibility

Brittany Richmond; University of Baltimore; UMBC; and Center for American Progress

Factors of Diversity

What Is Diversity?

There are few words in the English language that have more diverse interpretations than diversity. What does diversity mean? Better yet—what does diversity mean to you? And what does it mean to your best friend, your teacher, your parents, your religious leader, or the person standing behind you in a grocery store?

For each of us, diversity has unique meaning. Below are a few of the many definitions offered by college students at a 2010 conference on the topic of diversity. Which of these definitions rings out to you as most accurate and thoughtful? Which definitions could use some embellishment or clarification, in your opinion?

Diversity is a group of people who are different in the same place.

Diversity to me is the ability for differences to coexist together, with some type of mutual understanding or acceptance present. Acceptance of different viewpoints is key.

Tolerance of thought, ideas, people with differing viewpoints, backgrounds, and life experiences.

Anything that sets one individual apart from another.

People with different opinions, backgrounds (degrees and social experience), religious beliefs, political beliefs, sexual orientations, heritage, and life experience.

Dissimilar

Having a multitude of people from different backgrounds and cultures together in the same environment working for the same goals.

Difference in students’ background, especially race and gender.

Differences in characteristics of humans.

Diversity is a satisfying mix of ideas, cultures, races, genders, economic statuses and other characteristics necessary for promoting growth and learning among a group.

Diversity is the immersion and comprehensive integration of various cultures, experiences, and people.

Heterogeneity brings about opportunities to share, learn and grow from the journeys of others. Without it, limitations arise and knowledge is gained in the absence of understanding.

Diversity is not tolerance for difference but inclusion of those who are not the majority. It should not be measured as a count or a fraction—that is somehow demeaning. Success at maintaining diversity would be when we no longer ask if we are diverse enough, because it has become the norm, not remarkable.

Diversity means different things to different people, and it can be understood differently in different environments. In the context of your college experience, diversity generally refers to people around you who differ by race, culture, ethnicity, religion, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, abilities, opinions, political views, and in other ways. When it comes to diversity on the college campus, we also think about how groups interact with one another, given their differences (even if they’re just perceived differences.) How do diverse populations experience and explore their relationships?

“More and more organizations define diversity really broadly,” says Eric Peterson, who works on diversity issues for the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM). “Really, it’s any way any group of people can differ significantly from another group of people—appearance, sexual orientation, veteran status, your level in the organization. It has moved far beyond the legally protected categories that we’ve always looked at.”

Surface Diversity and Deep Diversity

Surface diversity and deep diversity are categories of personal attributes—or differences in attributes—that people perceive to exist between people or groups of people.

Surface-level diversity refers to differences you can generally observe in others, like ethnicity, race, gender, age, culture, language, disability, etc. You can quickly and easily observe these features in a person. And people often do just that, making subtle judgments at the same time, which can lead to bias or discrimination. For example, if a teacher believes that older students perform better than younger students, she may give slightly higher grades to the older students than the younger students. This bias is based on perception of the attribute of age, which is surface-level diversity.

Deep-level diversity, on the other hand, reflects differences that are less visible, like personality, attitude, beliefs, and values. These attributes are generally communicated verbally and nonverbally, so they are not easily noticeable or measurable. You may not detect deep-level diversity in a classmate, for example, until you get to know him or her, at which point you may find that you are either comfortable with these deeper character levels, or perhaps not. But once you gain this deeper level of awareness, you may focus less on surface diversity. For example: At the beginning of a term, a classmate belonging to a minority ethnic group, whose native language is not English (surface diversity), may be treated differently by fellow classmates in another ethnic group. But as the term gets under way, classmates begin discovering the person’s values and beliefs (deep-level diversity), which they find they are comfortable with. The surface-level attributes of language and perhaps skin color become more “transparent” (less noticeable) as comfort is gained with deep-level attributes.

Diversity in Education

Positive Effects of Diversity in an Educational Setting

Why does diversity matter in college? It matters because when you are exposed to new ideas, viewpoints, customs, and perspectives—which invariably happens when you come in contact with diverse groups of people—you expand your frame of reference for understanding the world. Your thinking becomes more open and global. You become comfortable working and interacting with people of all nationalities. You gain a new knowledge base as you learn from people who are different from yourself. You think “harder” and more creatively. You perceive in new ways, seeing issues and problems from new angles. You can absorb and consider a wider range of options, and your values may be enriched. In short, it contributes to your education.

Consider the following facts about diversity in the United States:

- More than half of all U.S. babies today are people of color, and by 2050 the U.S. will have no clear racial or ethnic majority. As communities of color are tomorrow’s leaders, college campuses play a major role in helping prepare these leaders.

- But in 2009, while 28 percent of Americans older than 25 years of age had a four-year college degree, only 17 percent of African Americans and 13 percent of Hispanics had a four-year degree. More must be done to adequately educate the population and help prepare students to enter the workforce.

- Today, people of color make up about 36 percent of the workforce (roughly one in three workers). But by 2050, half the workforce (one in two workers) will be a person of color. Again, college campuses can help navigate these changes.

All in all, diversity brings richness to relationships on campus and off campus, and it further prepares college students to thrive and work in a multicultural world. Diversity is fast becoming America’s middle name.

Questions to consider:

- What is identity?

- Can a person have more than one identity?

- Can identity be ambiguous?

- What are fluidity and intersectionality?

The multiple roles we play in life—student, sibling, employee, roommate, for example—are only a partial glimpse into our true identity. Right now, you may think, “I really don’t know what I want to be,” meaning you don’t know what you want to do for a living, but have you ever tried to define yourself in terms of the sum of your parts?

Social roles are those identities we assume in relationship to others. Our social roles tend to shift based on where we are and who we are with. Taking into account your social roles as well as your nationality, ethnicity, race, friends, gender, sexuality, beliefs, abilities, geography, etc., who are you?

Who Am I?

Popeye, a familiar 20th-century cartoon character, was a sailor-philosopher. He declared his own identity in a circular manner, landing us right where we started: “I am what I am and that’s all that I am.” Popeye proves his existence rather than help us identify him. It is his title, “The Sailor Man,” that tells us how Popeye operates in the social sphere.

According to the American Psychological Association, personal identity is an individual’s sense of self defined by (a) a set of physical, psychological, and interpersonal characteristics that is not wholly shared with any other person and (b) a range of affiliations (e.g., ethnicity) and social roles. Your identity is tied to the most dominant aspects of your background and personality.5 It determines the lens through which you see the world and the lens through which you receive information.

ACTIVITY

Complete the following statement using no more than four words:

I am _______________________________.

It is difficult to narrow down our identity to just a few options. One way to complete the statement would be to use gender and geography markers. For example, “I am a male New Englander” or “I am an American woman.” Assuming they are true, no one can argue against those identities, but do those statements represent everything or at least most things that identify the speakers? Probably not.

Try finishing the statement again by using as many words as you wish.

I am ____________________________________.

If you ended up with a long string of descriptors that would be hard for a new acquaintance to manage, don’t worry. Our identities are complex and reflect that we lead interesting and multifaceted lives.

To better understand identity, consider how social psychologists describe it. Social psychologists, those who study how social interactions take place, often categorize identity into four types: personal identity, role identity, social identity, and collective identity.

Personal identity captures what distinguishes one person from another based on life experiences. No two people, even identical twins, live the same life.

Role identity defines how we interact in certain situations. Our roles change from setting to setting, and so do our identities. At work you may be a supervisor; in the classroom you are a peer working collaboratively; at home, you may be the parent of a 10-year-old. In each setting, your bubbly personality may be the same, but how your coworkers, classmates, and family see you is different.

Social identity shapes our public lives by our awareness of how we relate to certain groups. For example, an individual might relate to or “identify with” Korean Americans, Chicagoans, Methodists, and Lakers fans. These identities influence our interactions with others. Upon meeting someone, for example, we look for connections as to how we are the same or different. Our awareness of who we are makes us behave a certain way in relation to others. If you identify as a hockey fan, you may feel an affinity for someone else who also loves the game.

Collective identity refers to how groups form around a common cause or belief. For example, individuals may bond over similar political ideologies or social movements. Their identity is as much a physical formation as a shared understanding of the issues they believe in. For example, many people consider themselves part of the collective energy surrounding the #metoo movement. Others may identify as fans of a specific type of entertainment such as Trekkies, fans of the Star Trek series.

“I am large. I contain multitudes.” Walt Whitman

In his epic poem Song of Myself, Walt Whitman writes, “Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself (I am large. I contain multitudes.).” Whitman was asserting and defending his shifting sense of self and identity. Those lines importantly point out that our identities may evolve over time. What we do and believe today may not be the same tomorrow. Further, at any one moment, the identities we claim may seem at odds with each other. Shifting identities are a part of personal growth. While we are figuring out who we truly are and what we believe, our sense of self and the image that others have of us may be unclear or ambiguous.

Many people are uncomfortable with identities that do not fit squarely into one category. How do you respond when someone’s identity or social role is unclear? Such ambiguity may challenge your sense of certainty about the roles that we all play in relationship to one another. Racial, ethnic, and gender ambiguity, in particular, can challenge some people’s sense of social order and social identity.

When we force others to choose only one category of identity (race, ethnicity, or gender, for example) to make ourselves feel comfortable, we do a disservice to the person who identifies with more than one group. For instance, people with multiracial ancestry are often told that they are too much of one and not enough of another.

The actor Keanu Reeves has a complex background. He was born in Beirut, Lebanon, to a white English mother and a father with Chinese-Hawaiian ancestry. His childhood was spent in Hawaii, Australia, New York, and Toronto. Reeves considers himself Canadian and has publicly acknowledged influences from all aspects of his heritage. Would you feel comfortable telling Keanu Reeves how he must identify racially and ethnically?

There is a question many people ask when they meet someone whom they cannot clearly identify by checking a specific identity box. Inappropriate or not, you have probably heard people ask, “What are you?” Would it surprise you if someone like Keanu Reeves shrugged and answered, “I’m just me”?

Malcom Gladwell is an author of five New York Times best-sellers and is hailed as one of Foreign Policy’s Top Global Thinkers. He has spoken on his experience with identity as well. Gladwell has a black Jamaican mother and a white Irish father. He often tells the story of how the perception of his hair has allowed him to straddle racial groups. As long as he kept his hair cut very short, his fair skin obscured his black ancestry, and he was most often perceived as white. However, once he let his hair grow long into a curly Afro style, Gladwell says he began being pulled over for speeding tickets and stopped at airport check-ins. His racial expression carried serious consequences.

Gender

More and more, gender is also a diversity category that we increasingly understand to be less clearly defined. Some people identify themselves as gender fluid or non-binary. “Binary” refers to the notion that gender is only one of two possibilities, male or female. Fluidity suggests that there is a range or continuum of expression. Gender fluidity acknowledges that a person may vacillate between male and female identity.

Asia Kate Dillon is an American actor and the first non-binary actor to perform in a major television show with their roles on Orange is the New Black and Billions. In an article about the actor, a reporter conducting the interview describes his struggle with trying to describe Dillon to the manager of the restaurant where the two planned to meet. The reporter and the manger struggle with describing someone who does not fit a pre-defined notion of gender identity. Imagine the situation: You’re meeting someone at a restaurant for the first time, and you need to describe the person to a manager. Typically, the person’s gender would be a part of the description, but what if the person cannot be described as a man or a woman?

Within any group, individuals obviously have a right to define themselves; however, collectively, a group’s self-determination is also important. The history of black Americans demonstrates a progression of self-determined labels: Negro, Afro-American, colored, black, African American. Similarly, in the nonbinary community, self-described labels have evolved. Nouns such as genderqueer and pronouns such as hir, ze, and Mx. (instead of Miss, Mrs. or Mr.) have entered not only our informal lexicon, but the dictionary as well.

Merriam-Webster’s dictionary includes a definition of “they” that denotes a nonbinary identity, that is, someone who fluidly moves between male and female identities.

Transgender men and women were assigned a gender identity at birth that does not fit their true identity. Even though our culture is increasingly giving space to non-heteronormative (straight) people to speak out and live openly, they do so at a risk. Violence against gay, nonbinary, and transgender people occurs at more frequent rates than for other groups.

To make ourselves feel comfortable, we often want people to fall into specific categories so that our own social identity is clear. However, instead of asking someone to make us feel comfortable, we should accept the identity people choose for themselves. Cultural competency includes respectfully addressing individuals as they ask to be addressed.

Table Gender Pronoun Examples

| Subjective | Objective | Possessive | Reflexive | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| She | Her | Hers | Herself | She is speaking. I listened to her. The backpack is hers. |

| He | Him | His | Himself | He is speaking. I listened to him. The backpack is his. |

| They | Them | Theirs | Themself | They are speaking. I listened to them. The backpack is theirs. |

| Ze | Hir/Zir | Hirs/Zirs | Hirself/Zirself | Ze is speaking. I listened to hir. The backpack is zirs. |

Intersectionality

The many layers of our multiple identities do not fit together like puzzle pieces with clear boundaries between one piece and another. Our identities overlap, creating a combined identity in which one aspect is inseparable from the next.

The term intersectionality was coined by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989 to describe how the experience of black women was a unique combination of gender and race that could not be divided into two separate identities. In other words, this group could not be seen solely as women or solely as black; where their identities overlapped is considered the “intersection,” or crossroads, where identities combine in specific and inseparable ways.

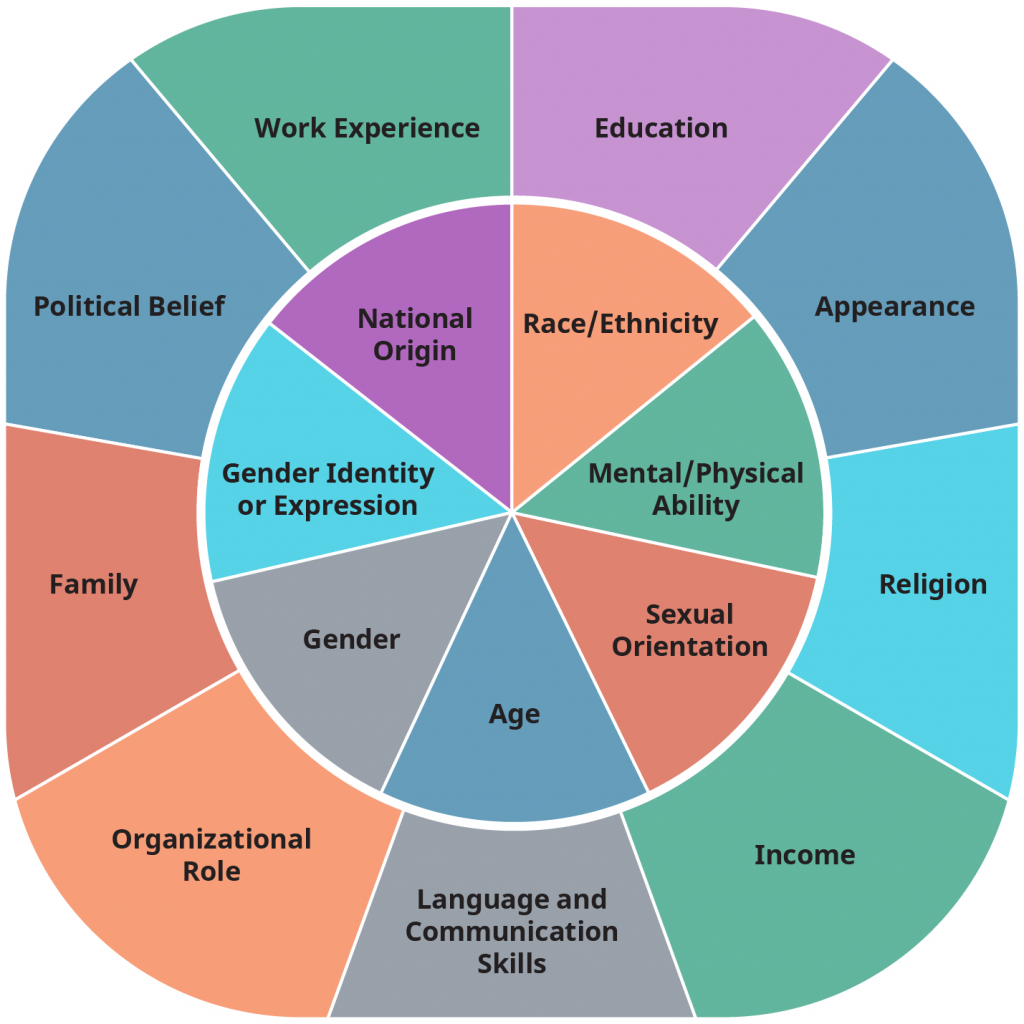

Figure: Our identities are formed by dozens of factors, sometimes represented in intersection wheels. Consider the subset of identity elements represented here. Generally, the outer ring are elements that may change relatively often, while the inner circle are often considered more permanent. (There are certainly exceptions.) How does each contribute to who you are, and how would possible change alter your self-defined identity?

Intersectionality and awareness of intersectionality can drive societal change, both in how people see themselves and how they interact with others. That experience can be very inward-facing, or can be more external. It can also lead to debate and challenges. For example, the term “Latinx” is growing in use because it is seen as more inclusive than “Latino/Latina,” but some people—including scholars and advocates—lay out substantive arguments against its use. While the debate continues, it serves as an important reminder of a key element of intersectionality: Never assume that all people in a certain group or population feel the same way. Why not? Because people are more than any one element of their identity; they are defined by more than their race, color, geographic origin, gender, or socio-economic status. The overlapping aspects of each person’s identity and experiences will create a unique perspective.

ANALYSIS QUESTION

Consider the intersectionality of race, gender, and sexuality; religion,

ANALYSIS QUESTION

Consider the intersectionality of race, gender, and sexuality; religion, ethnicity, and geography; military experience; age and socioeconomic status; and many other ways our identities overlap. Consider how these overlap in you.

Do you know people who talk easily about their various identities? How does it inform the way you interact with them?

Cultural Competency

As a college student, you are likely to find yourself in diverse classrooms, organizations, and— eventually—workplaces. It is important to prepare yourself to be able to adapt to diverse environments. Cultural competency can be defined as the ability to recognize and adapt to cultural differences and similarities. It involves “(a) the cultivation of deep cultural self-awareness and understanding (i.e., how one’s own beliefs, values, perceptions, interpretations, judgments, and behaviors are influenced by one’s cultural community or communities) and (b) increased cultural other-understanding (i.e., comprehension of the different ways people from other cultural groups make sense of and respond to the presence of cultural differences).”

In other words, cultural competency requires you to be aware of your own cultural practices, values, and experiences, and to be able to read, interpret, and respond to those of others. Such awareness will help you successfully navigate the cultural differences you will encounter in diverse environments. Cultural competency is critical to working and building relationships with people from different cultures; it is so critical, in fact, that it is now one of the most highly desired skills in the modern workforce.

In the following video, representatives from Rutgers University Behavioral Health Care elaborate on the concept of cultural competency:

Cultural Competency at Rutgers University Behavioral Health Care

We don’t automatically understand differences among people and celebrate the value of those differences. Cultural competency is a skill that you can learn and improve upon over time and with practice. What actions can you take to build your cultural competency skills?

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Diversity refers to a great variety of human characteristics and ways in which people differ.

- Surface-level diversity refers to characteristics you can easily observe, while deep-level diversity refers to attributes that are not visible and must be communicated in order to understand.

- Cultural competency is the ability to recognize and adapt to cultural differences and similarities.

- Diverse environments expose you to new perspectives and can help deepen your learning.