4 College Level Critical Thinking, Reading and Decision Making

Jeremy Boettinger; https://openstax.org/books/college-success@10.2/pages/2-3-its-all-in-the-mindset; and Foundations of Academic Success: Words of Wisdom

Words of Wisdom: Thinking Critically and Creatively

Critical and creative thinking skills are perhaps the most fundamental skills involved in making judgments and solving problems. They are some of the most important skills I have ever developed. I use them everyday and continue to work to improve them both.

The ability to think critically about a matter—to analyze a question, situation, or problem down to its most basic parts—is what helps us evaluate the accuracy and truthfulness of statements, claims, and information we read and hear. It is the sharp knife that, when honed, separates fact from fiction, honesty from lies, and the accurate from the misleading. We all use this skill to one degree or another almost every day. For example, we use critical thinking every day as we consider the latest consumer products and why one particular product is the best among its peers. Is it a quality product because a celebrity endorses it? Because a lot of other people may have used it? Because it is made by one company versus another? Or perhaps because it is made in one country or another? These are questions representative of critical thinking.

The academic setting demands more of us in terms of critical thinking than everyday life. It demands that we evaluate information and analyze a myriad of issues. It is the environment where our critical thinking skills can be the difference between success and failure. In this environment we must consider information in an analytical, critical manner. We must ask questions—What is the source of this information? Is this source an expert one and what makes it so? Are there multiple perspectives to consider on an issue? Do multiple sources agree or disagree on an issue? Does quality research substantiate information or opinion? Do I have any personal biases that may affect my consideration of this information? It is only through purposeful, frequent, intentional questioning such as this that we can sharpen our critical thinking skills and improve as students, learners, and researchers. Developing my critical thinking skills over a twenty year period as a student in higher education enabled me to complete a quantitative dissertation, including analyzing research and completing statistical analysis, and earning my Ph.D. in 2014.

While critical thinking analyzes information and roots out the true nature and facets of problems, it is creative thinking that drives progress forward when it comes to solving these problems.

Exceptional creative thinkers are people that invent new solutions to existing problems that do not rely on past or current solutions. They are the ones who invent solution C when everyone else is still arguing between A and B. Creative thinking skills involve using strategies to clear the mind so that our thoughts and ideas can transcend the current limitations of a problem and allow us to see beyond barriers that prevent new solutions from being found.

Brainstorming is the simplest example of intentional creative thinking that most people have tried at least once. With the quick generation of many ideas at once we can block-out our brain’s natural tendency to limit our solution-generating abilities so we can access and combine many possible solutions/thoughts and invent new ones. It is sort of like sprinting through a race’s finish line only to find there is new track on the other side and we can keep going, if we choose. As with critical thinking, higher education both demands creative thinking from us and is the perfect place to practice and develop the skill. Everything from word problems in a math class, to opinion or persuasive speeches and papers, call upon our creative thinking skills to generate new solutions and perspectives in response to our professor’s demands. Creative thinking skills ask questions such as—What if? Why not? What else is out there? Can I combine perspectives/solutions? What is something no one else has brought-up? What is being forgotten/ignored? What about ______? It is the opening of doors and options that follows problem-identification.

Consider an assignment that required you to compare two different authors on the topic of education and select and defend one as better. Now add to this scenario that your professor clearly prefers one author over the other. While critical thinking can get you as far as identifying the similarities and differences between these authors and evaluating their merits, it is creative thinking that you must use if you wish to challenge your professor’s opinion and invent new perspectives on the authors that have not previously been considered.

So, what can we do to develop our critical and creative thinking skills? Although many students may dislike it, group work is an excellent way to develop our thinking skills. Many times I have heard from students their disdain for working in groups based on scheduling, varied levels of commitment to the group or project, and personality conflicts too, of course. True—it’s not always easy, but that is why it is so effective. When we work collaboratively on a project or problem we bring many brains to bear on a subject. These different brains will naturally develop varied ways of solving or explaining problems and examining information. To the observant individual we see that this places us in a constant state of back and forth critical/creative thinking modes.

For example, in group work we are simultaneously analyzing information and generating solutions on our own, while challenging other’s analyses/ideas and responding to challenges to our own analyses/ideas. This is part of why students tend to avoid group work—it challenges us as thinkers and forces us to analyze others while defending ourselves, which is not something we are used to or comfortable with as most of our educational experiences involve solo work. Your professors know this—that’s why we assign it—to help you grow as students, learners, and thinkers!

Performance vs. Learning Goals

As you have discovered in this chapter, much of our ability to learn is governed by our motivations and goals. What has not yet been covered in detail has been how sometimes hidden goals or mindsets can impact the learning process. In truth, we all have goals that we might not be fully aware of, or if we are aware of them, we might not understand how they help or restrict our ability to learn. An illustration of this can be seen in a comparison of a student that has performance-based goals with a student that has learning-based goals.

If you are a student with strict performance goals, your primary psychological concern might be to appear intelligent to others. At first, this might not seem to be a bad thing for college, but it can truly limit your ability to move forward in your own learning. Instead, you would tend to play it safe without even realizing it. For example, a student who is strictly performance-goal-oriented will often only says things in a classroom discussion when they think it will make them look knowledgeable to the instructor or their classmates. For example, a performance-oriented student might ask a question that she knows is beyond the topic being covered (e.g., asking about the economics of Japanese whaling while discussing the book Moby Dick in an American literature course). Rarely will they ask a question in class because they actually do not understand a concept. Instead they will ask questions that make them look intelligent to others or in an effort to “stump the teacher.” When they do finally ask an honest question, it may be because they are more afraid that their lack of understanding will result in a poor performance on an exam rather than simply wanting to learn.

If you are a student who is driven by learning goals, your interactions in classroom discussions are usually quite different. You see the opportunity to share ideas and ask questions as a way to gain knowledge quickly. In a classroom discussion you can ask for clarification immediately if you don’t quite understand what is being discussed. If you are a person guided by learning goals, you are less worried about what others think since you are there to learn and you see that as the most important goal.

Another example where the difference between the two mindsets is clear can be found in assignments and other coursework. If you are a student who is more concerned about performance, you may avoid work that is challenging. You will take the “easy A” route by relying on what you already know. You will not step out of your comfort zone because your psychological goals are based on approval of your performance instead of being motivated by learning.

This is very different from a student with a learning-based psychology. If you are a student who is motivated by learning goals, you may actively seek challenging assignments, and you will put a great deal of effort into using the assignment to expand on what you already know. While getting a good grade is important to you, what is even more important is the learning itself.

If you find that you sometimes lean toward performance-based goals, do not feel discouraged. Many of the best students tend to initially focus on performance until they begin to see the ways it can restrict their learning. The key to switching to learning-based goals is often simply a matter of first recognizing the difference and seeing how making a change can positively impact your own learning.

What follows in this section is a more in-depth look at the difference between performance- and learning-based goals. This is followed by an exercise that will give you the opportunity to identify, analyze, and determine a positive course of action in a situation where you believe you could improve in this area.

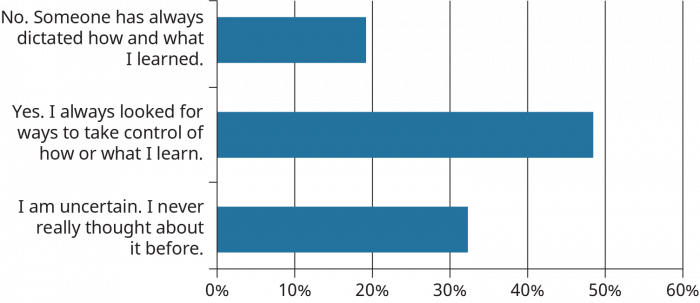

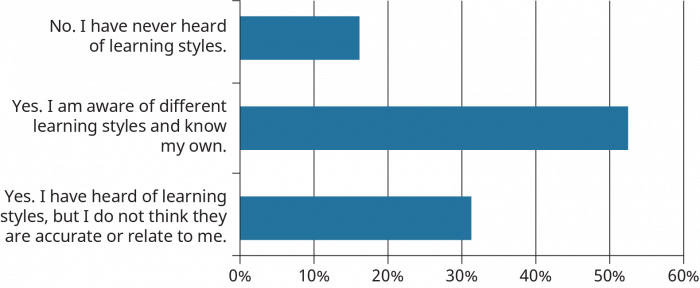

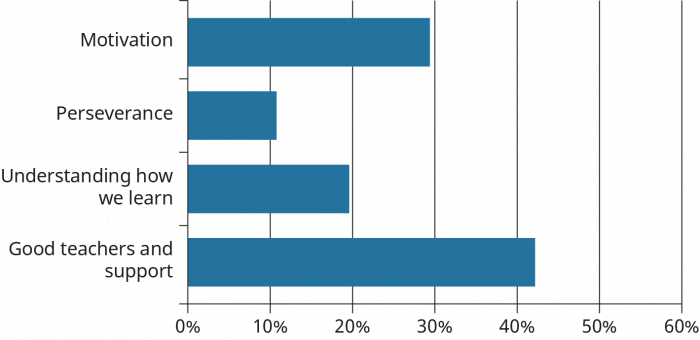

What Students Say

- In the past, did you feel like you had control over your own learning?

- No. Someone has always dictated how and what I learned.

- Yes. I always look for ways to take control of what and how I learned.

- I am uncertain. I never thought about it before.

- Have you ever heard of learning styles or do you know your own learning style?

- No. I have never heard of learning styles.

- Yes. I have heard of learning styles and know my own.

- Yes. I have heard of learning styles, but I don’t think they’re accurate or relate to me.

- Which factors other than intelligence do you think have the greatest influence on learning?

- Motivation

- Perseverance

- Understanding how I learn

- Good teachers and support

You can also take the anonymous What Students Say surveys to add your voice to this textbook. Your responses will be included in updates.

Students offered their views on these questions, and the results are displayed in the graphs below.

In the past, did you feel like you had control over your own learning?

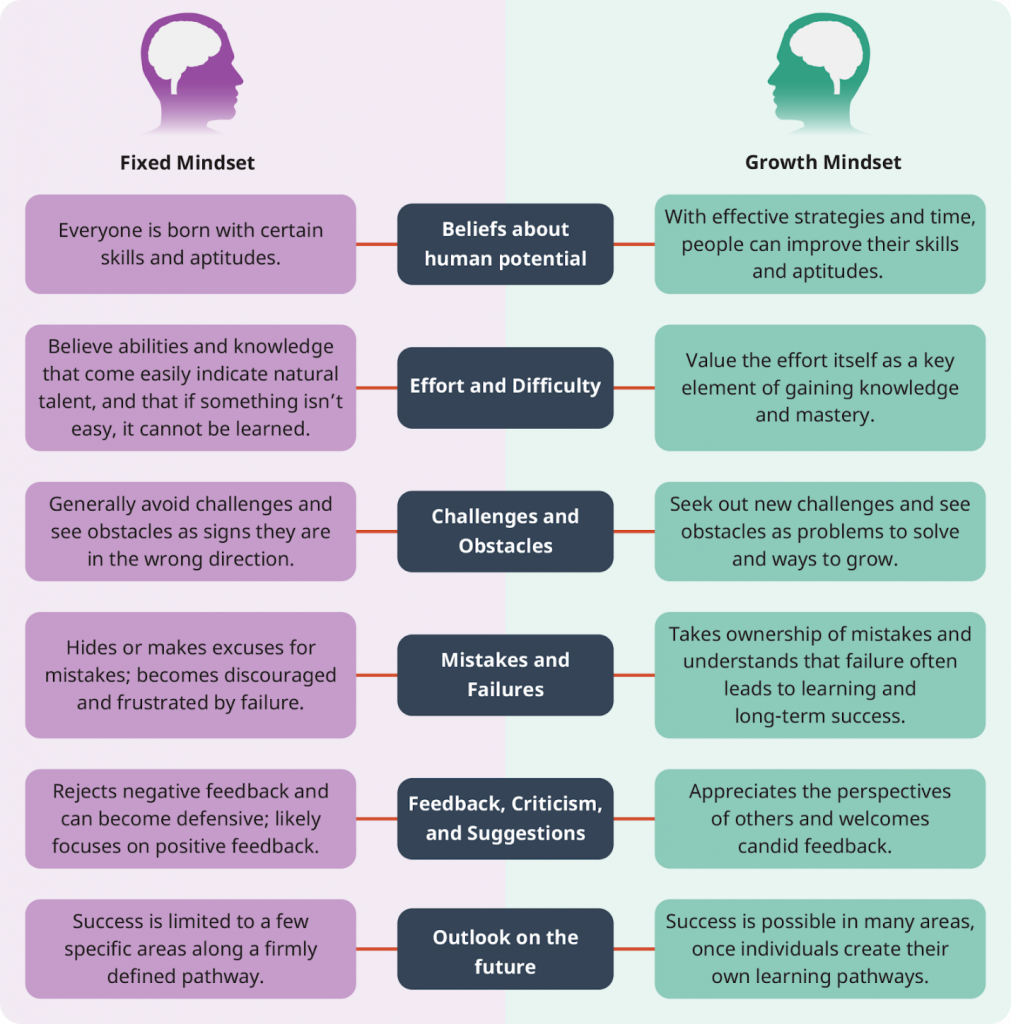

Fixed vs. Growth Mindset

The research-based model of these two mindsets and their influence on learning was presented in 1988 by Carol Dweck.7 In Dr. Dweck’s work, she determined that a student’s perception about their own learning accompanied by a broader goal of learning had a significant influence on their ability to overcome challenges and grow in knowledge and ability. This has become known as the Fixed vs. Growth Mindset model. In this model, the performance-goal-oriented student is represented by the fixed mindset, while the learning-goal-oriented student is represented by the growth mindset.

In the following graphic, based on Dr. Dweck’s research, you can see how many of the components associated with learning are impacted by these two mindsets.

The Growth Mindset and Lessons About Failing

Something you may have noticed is that a growth mindset would tend to give a learner grit and persistence. If you had learning as your major goal, you would normally keep trying to attain that goal even if it took you multiple attempts. Not only that, but if you learned a little bit more with each try you would see each attempt as a success, even if you had not achieved complete mastery of whatever it was you were working to learn.

With that in mind, it should come as no surprise that Dr. Dweck found that those people who believed their abilities could change through learning (growth vs. a fixed mindset) readily accepted learning challenges and persisted despite early failures.

Improving Your Ability to Learn

As strange as it may seem, research into fixed vs. growth mindsets has shown that if you believe you can learn something new, you greatly improve your ability to learn. At first, this may seem like the sort of feel-good advice we often encounter in social media posts or quotes that are intended to inspire or motivate us (e.g., believe in yourself!), but in looking at the differences outlined between a fixed and a growth mindset, you can see how each part of the growth mindset path would increase your probability of success when it came to learning.

Activity

Very few people have a strict fixed or growth mindset all of the time. Often we tend to lean one way or another in certain situations. For example, a person trying to improve their ability in a sport they enjoy may exhibit all of the growth mindset traits and characteristics, but they find themselves blocked in a fixed mindset when they try to learn something in another area like computer programming or arithmetic.

In this exercise, do a little self-analysis and think of some areas where you may find yourself hindered by a fixed mindset. Using the outline presented below, in the far right column, write down how you can change your own behavior for each of the parts of the learning process. What will you do to move from a fixed to a growth mindset? For example, say you were trying to learn to play a musical instrument. In the Challenges row, you might pursue a growth path by trying to play increasingly more difficult songs rather than sticking to the easy ones you have already mastered. In the Criticism row, you might take someone’s comment about a weakness in timing as a motivation for you to practice with a metronome. For Success of others you could take inspiration from a famous musician that is considered a master and study their techniques.

Whatever it is that you decide you want to use for your analysis, apply each of the Growth characteristics to determine a course of action to improve.

| Parts of the learning process | Growth characteristic | What will you do to adopt a growth mindset? |

| Challenges | Embraces challenges | |

| Obstacles | Persists despite setbacks | |

| Effort | Sees effort as a path to success | |

| Criticism | Learns from criticism | |

| Success of Others | Finds learning and inspiration in the success of others |

Applying What You Know about Learning

Another useful part of being an informed learner is recognizing that as a college student you will have many choices when it comes to learning. Looking back at the Uses and Gratification model, you’ll discover that your motivations as well as your choices in how you interact with learning activities can make a significant difference in not only what you learn, but how you learn. By being aware of a few learning theories, students can take initiative and tailor their own learning so that it best benefits them and meets their main needs.

Student Profile

“My seating choice significantly affects my learning. Sitting at a desk where the professor’s voice can be heard clearly helps me better understand the subject; and ensuring I have a clear view helps me take notes. Therefore, sitting in the front of the classroom should be a “go to” strategy while attending college. It will keep you focused and attentive throughout the lecture. Also, sitting towards the front of the classroom limits the tendency to be on check my phone.”

—Luis Angel Ochoa, Westchester Community College

Making Decisions about Your Own Learning

As a learner, the kinds of materials, study activities, and assignments that work best for you will derive from your own experiences and needs (needs that are both short-term as well as those that fulfill long-term goals). In order to make your learning better suited to meet these needs, you can use the knowledge you have gained about UGT and other learning theories to make decisions concerning your own learning. These decisions can include personal choices in learning materials, how and when you study, and most importantly, taking ownership of your learning activities as an active participant and decision maker. In fact, one of the main principles emphasized in this chapter is that students not only benefit from being involved in planning their instruction, but learners also gain by continually evaluating the actual success of that instruction. In other words: Does this work for me? Am I learning what I need to by doing it this way?

While it may not always be possible to control every component of your learning over an entire degree program, you can take every opportunity to influence learning activities so they work to your best advantage. What follows are several examples of how this can be done by making decisions about your learning activities based on what you have already learned in this chapter.

Make Mistakes Safe

Create an environment for yourself where mistakes are safe and mistakes are expected as just another part of learning. This practice ties back to the principles you learned in the section on grit and persistence. The key is to allow yourself the opportunity to make mistakes and learn from them before they become a part of your grades. You can do this by creating your own learning activities that you design to do just that. An example of this might be taking practice quizzes on your own, outside of the more formal course activities. The quizzes could be something you find in your textbook, something you find online, or something that you develop with a partner. In the latter case you would arrange with a classmate for each of you to produce a quiz and then exchange them. That particular exercise would serve double learning duty, since to create a good quiz you would need to learn the main concepts of the subject, and answering the questions on your partner’s quiz might help you identify areas where you need more knowledge.

The main idea with this sort of practice is that you are creating a safe environment where you can make mistakes and learn from them before those mistakes can negatively impact your success in the course. Better to make mistakes on a practice run than on any kind of assignment or exam that can heavily influence your final grade in a course.

Make Everything Problem Centered

When working through a learning activity, the practical act of problem-solving is a good strategy. Problem-solving, as an approach, can give a learning activity more meaning and motivation for you, as a learner. Whenever possible it is to your advantage to turn an assignment or learning task into a problem you are trying to solve or something you are trying to accomplish.

In essence, you do this by deciding on some purpose for the assignment (other than just completing the assignment itself). An example of this would be taking the classic college term paper and writing it in a way that solves a problem you are already interested in.

Typically, many students treat a term paper as a collection of requirements that must be fulfilled—the paper must be on a certain topic; it should include an introduction section, a body, a closing, and a bibliography; it should be so many pages long, etc. With this approach, the student is simply completing a checklist of attributes and components dictated by the instructor, but other than that, there is no reason for the paper to exist.

Instead, writing it to solve a problem gives the paper purpose and meaning. For example, if you were to write a paper with the purpose of informing the reader about a topic they knew little about, that purpose would influence not only how you wrote the paper but would also help you make decisions on what information to include. It would also influence how you would structure information in the paper so that the reader might best learn what you were teaching them. Another example would be to write a paper to persuade the reader about a certain opinion or way of looking at things. In other words, your paper now has a purpose rather than just reporting facts on the subject. Obviously, you would still meet the format requirements of the paper, such as number of pages and inclusion of a bibliography, but now you do that in a way that helps to solve your problem.

Make It Occupation Related

Much like making assignments problem centered, you will also do well when your learning activities have meaning for your profession or major area of study. This can take the form of simply understanding how the things you are learning are important to your occupation, or it can include the decision to do assignments in a way that can be directly applied to your career. If an exercise seems pointless and possibly unrelated to your long-term goals, you will be much less motivated by the learning activity.

An example of understanding how a specific school topic impacts your occupation future would be that of a nursing student in an algebra course. At first, algebra might seem unrelated to the field of nursing, but if the nursing student recognizes that drug dosage calculations are critical to patient safety and that algebra can help them in that area, there is a much stronger motivation to learn the subject.

In the case of making a decision to apply assignments directly to your field, you can look for ways to use learning activities to build upon other areas or emulate tasks that would be required in your profession. Examples of this might be a communication student giving a presentation in a speech course on how the Internet has changed corporate advertising strategies, or an accounting student doing statistics research for an environmental studies course. Whenever possible, it is even better to use assignments to produce things that are much like what you will be doing in your chosen career. An example of this would be a graphic design student taking the opportunity to create an infographic or other supporting visual elements as a part of an assignment for another course. In cases where this is possible, it is always best to discuss your ideas with your instructor to make certain what you intend will still meet the requirements of the assignment.

Managing Your Time

One of the most common traits of college students is the constraint on their time. As adults, we do not always have the luxury of attending school without other demands on our time. Because of this, we must become efficient with our use of time, and it is important that we maximize our learning activities to be most effective. In fact, time management is so important that there is an entire chapter in this text dedicated to it. When you can, refer to that chapter to learn more about time management concepts and techniques that can be very useful.

Instructors as Learning Partners

In K-12 education, the instructor often has the dual role of both teacher and authority figure for students. Children come to expect their teachers to tell them what to do, how to do it, and when to do it. College learners, on the other hand, seem to work better when they begin to think of their instructors as respected experts that are partners in their education. The change in the relationship for you as a learner accomplishes several things: it gives you ownership and decision-making ability in your own learning, and it enables you to personalize your learning experience to best fit your own needs. For the instructor, it gives them the opportunity to help you meet your own needs and expectations in a rich experience, rather than focusing all of their time on trying to get information to you.

The way to develop learning partnerships is through direct communication with your instructors. If there is something you do not understand or need to know more about, go directly to them. When you have ideas about how you can personalize assignments or explore areas of the subject that interest you or better fit your needs, ask them about it. Ask your instructors for guidance and recommendations, and above all, demonstrate to them that you are taking a direct interest in your own learning. Most instructors are thrilled when they encounter students that want to take ownership of their own learning, and they will gladly become a resourceful guide for you.

Application

Applying What You Know about Learning to What You Are Doing:

In this activity, you will work with an upcoming assignment from one of your courses—preferably something you might be dreading or are at least less than enthusiastic about working on. You will see if there is anything you can apply to the assignment from what you know about learning that might make it more interesting.

In the table below are several attributes that college students generally prefer in their learning activities, listed in the far left column. As you think about your assignment, consider whether or not it already possesses the attribute. If it does, go on to the next row. If it does not, see if there is some way you can approach the assignment so that it does follow preferred learning attributes; write that down in the last column, to the far right.

| Does it …? | Yes | No | What you can do to turn the assignment into something that is better suited to you as a learner? |

| Does it allow you to make decisions about your own learning? | In essence, you are doing this right now. You are making decisions on how you can make your assignment more effective for you. | ||

| Does it allow you to make mistakes without adversely affecting your grade? | Hints: Are there ways for you to practice? Can you create a series of drafts for the assignment and get feedback? | ||

| Is it centered on solving a problem? | Hint: Can you turn the assignment into something that solves a problem? An example would be making a presentation that actually educated others rather than just covered what you may have learned. | ||

| Is it related to your chosen occupation in any way? | Hint: Can you turn the assignment into something you might actually do as a part of your profession or make it about your profession? Examples might be creating an informative poster for the workplace or writing a paper on new trends in your profession. | ||

| Does it allow you to manage the time you work on it? | More than likely the answer here will be “yes,” but you can plan how you will do it. For more information on this, see the chapter on time management. | ||

| Does it allow interaction with your instructor as a learning partner? | Hint: Talking to your instructor about the ideas you have for making this assignment more personalized accomplishes this exact thing. |

The Hidden Curriculum

The hidden curriculum is a phrase used to cover a wide variety of circumstances at school that can influence learning and affect your experience. Sometimes called the invisible curriculum, it varies by institution and can be thought of as a set of unwritten rules or expectations.

Situation: According to your syllabus, your history professor is lecturing on the chapter that covers the stock market crash of 1929 on Tuesday of next week.

Sounds pretty straightforward and common. Your professor lectures on a topic and you will be there to hear it. However, there are some unwritten rules, or hidden curriculum, that are not likely to be communicated. Can you guess what they may be?

- What is an unwritten rule about what you should be doing before attending class?

- What is an unwritten rule about what you should be doing in class?

- What is an unwritten rule about what you should be doing after class?

- What is an unwritten rule if you are not able to attend that class?

Some of your answers could have included the following:

| Before class: | read the assigned chapter, take notes, record any questions you have about the reading |

| During class: | take detailed notes, ask critical thinking or clarifying questions, avoid distractions, bring your book and your reading notes |

| After class: | reorganize your notes in relation to your other notes, start the studying process by testing yourself on the material, make an appointment with your professor if you are not clear on a concept |

| Absent: | communicate with the professor, get notes from a classmate, make sure you did not miss anything important in your notes |

The expectations before, during, and after class, as well as what you should do if you miss class, are often unspoken because many professors assume you already know and do these things or because they feel you should figure them out on your own. Nonetheless, some students struggle at first because they don’t know about these habits, behaviors, and strategies. But once they learn them, they are able to meet them with ease.

While the previous example may seem obvious once they’ve been pointed out, most instances of the invisible curriculum are complex and require a bit of critical thinking to uncover. What follows are some common but often overlooked examples of this invisible curriculum.

One example of a hidden curriculum could be found in the beliefs of your professor. Some professors may refuse to reveal their personal beliefs to avoid your writing toward their bias rather than presenting a cogent argument of your own. Other professors may be outspoken about their beliefs to force you to consider and possibly defend your own position. As a result, you may be influenced by those opinions which can then influence your learning, but not as an official part of your study.

Other examples of how this hidden curriculum might not always be so easily identified can be found in classroom arrangements or even scheduling. To better understand this, imagine two different classes on the exact same subject and taught by the same instructor. One class is held in a large lecture hall and has over 100 students in it, while the other meets in a small classroom and has fewer than 20 students. In the smaller class, there is time for all of the students to participate in discussions as a learning activity, and they receive the benefit of being able to talk about their ideas and the lessons through direct interaction with each other and the professor. In the larger class, there is simply not enough time for all 100 students to each discuss their thoughts. On the flip side, most professors who teach lecture classes use technology to give them constant feedback on how well students understand a given subject. If the data suggests more time should be spent, these professors discover this in real time and can adapt the class accordingly.

Another instance where class circumstances might heavily influence student learning could be found in the class schedule. If the class was scheduled to meet on Mondays and Wednesdays and the due date for assignments was always on Monday, those students would benefit from having the weekend to finalize their work before handing it in. If the class met on a different day, students might not have as much free time just before handing in the assignment. The obvious solution would be better planning and time management to complete assignments in advance of due dates, but nonetheless, conditions caused by scheduling may still impact student learning.

Working Within the Hidden Curriculum

The first step in dealing with the hidden curriculum is to recognize it and understand how it can influence your learning. After any specific situation has been identified, the next step is to figure out how to work around the circumstances to either take advantage of any benefits or to remove any roadblocks.

To illustrate this, here are some possible solutions to the situations given as examples earlier in this section:

Prevailing Opinions—Simply put, you are going to encounter instructors and learning activities that you sometimes agree with and sometimes do not. The key is to learn from them regardless. In either case, take ownership of your learning and even make an effort to learn about other perspectives, even if it is only for your own education on the matter. There is no better time to expose yourself to other opinions and philosophies than in college. In fact, many would say that this is a significant part of the college experience. With a growth mindset, it is easy to view everything as a learning opportunity.

Classroom Circumstances—These kinds of circumstances often require a more structured approach to turn the situation to your advantage, but they also usually have the most obvious solutions. In the example of the large class, you might find yourself limited in the ability to participate in classroom discussions because of so many other students. The way around that would be to speak to several classmates and create your own discussion group. You could set up a time to meet, or you could take a different route by using technology such as an online discussion board, a Skype session, or even a group text. Several of the technologically based solutions might even be better than an in-class discussion since you do not all have to be present at the same time. The discussion can be something that occurs all week long, giving everyone the time to think through their ideas and responses.

Again, the main point is to first spot those things in the hidden curriculum that might put your learning at a disadvantage and devise a solution that either reduces the negative impact or even becomes a learning advantage.