Chapter 10: Financial Literacy

Jeremy Boettinger and openstax.org/books/college-success

What Would You Do?

Everything was working out for Elan. They got into the college they wanted to, and some friends were planning to attend as well. They felt like an adult, and were looking forward to new freedoms and opportunities. Elan’s parents let them get a credit card after high school graduation. Elan shared an apartment with their friends just off campus, and was able to get where they needed to go because they had a car. Elan had also saved over $1,000 from gifts and a summer job. They needed a new laptop.

Elan planned to stay within set limits. They went to the store found a very knowledgeable salesperson, Jermain, who said he knew exactly what Elan needed. Jermain pointed out that the laptop in Elan’s budget would do schoolwork just fine, but it was not as powerful as the best top-of-the line unit with advanced gaming features. Plus, the better computer came with new headphones! Jermain suggested that Elan could later sell the computer to incoming students. (Most freshmen bought used computers if they did not have one when they came to school.) The high-powered computer was $2,000, though, and Elan didn’t have that much money. Maybe they should use the credit card? Maybe their new part-time job would pay for it. But Jermain arranged for a small down payment and monthly payments of only $100. That did not seem too bad to Elan. The future looked bright!

At least, that’s what Elan thought. They soon realized that working more hours meant fewer hours to study. Meanwhile, Elan’s rent and gas usage went up, and, as a young car owner, their insurance was through the roof. Only three months into the first semester, Elan missed a payment on the laptop and accrued a late fee. They put the next laptop payment on the credit card. Soon, Elan was alternating payments between the credit card, laptop, and car, building up interest and late charges. Now Elan was having trouble paying their rent and started getting calls from creditors. Everything had seemed so promising. Elan didn’t know where they had gone wrong.

Elan comes to you and shares the situation. They ask, “What could I have done differently?”

This chapter offers you insight into your finances so that you can make good decisions and avoid costly mistakes. We all face chances to spend money and try to get what we want. Many think only about now and not next month, next year, or ten years from now, but our behavior now has consequences later. Not everyone can own all the latest technology, drive their dream car, continually invest for their retirement, or live in the perfect home at this moment. But by understanding the different components of earning money, banking, credit, and budgeting, you can begin working toward your personal and financial goals. We’ll also discuss a related topic, safeguarding your accounts and personal information, which is critical to protecting everything you’ve worked for. By the end of this chapter, you will have good insights for Elan . . . and you!

Education Debt: Paying for College

“An investment in knowledge always pays the best interest.”

—Benjamin Franklin, The Way to Wealth: Ben Franklin on Money and Success

As you progress through your college experience, the cost of college can add up rapidly. Worse, your anxiety about the cost of college may rise faster as you hear about the rising costs of college and horror stories regarding the “student loan crisis.” It is important to remember that you are in control of your choices and the cost of your college experience, and you do not have to be a sad statistic.

Education Choices

Education is vital to living. Education starts at the beginning of our life, and as we grow, we learn language, sharing, and to look both ways before crossing the street. We also generally pursue a secular or public education that often ends at high school graduation. After that, we have many choices, including getting a job and stopping our education, working at a trade or business started by our parents and bypassing additional schooling, earning a certificate from a community college or four-year college or university, earning a two-year or associate degree from one of the same schools, and completing a bachelor’s or advanced degree at a college or university. We can choose to attend a public or private school. We can live at home or on a campus.

Each of these choices impacts our debt, happiness, and earning power. The average income goes up with an increase in education, but that is not an absolute rule. The New York Federal Reserve Bank reported in 2017 that approximately 34 percent of college graduates worked in a job that did not require a college degree,14 and in 2013, CNN Money reported on a study from Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce showing that nearly 30 percent of Americans with two-year degrees are now earning more than graduates with bachelor’s degrees.15 Of course, many well-paying occupations do require a bachelor’s or master’s degree. You have started on a path that may be perfect for you, but you may also choose to make adjustments.

College success from a financial perspective means that you must:

- Know the total cost of the education

- Consider job market trends

- Work hard at school during the education

- Pursue ways to reduce costs

Most importantly: Buy only the amount of education that returns more than you invest.

According to US News & World Report, the average cost of college (including university) tuition and fees varies widely. In-state colleges average $9,716 while out-of-state students pay $21,629 for the same state college. Private colleges average $35,676. The local community college averages approximately $3,726. On-campus housing and meals, if available, can add approximately $10,000 per year.16 See the table below, and create your own chart after you research.

Sample College Costs

| Type of School | Annual Tuition without Housing | Tuition If Living on Campus | Total Cost at Planned Completion |

| Community College (2 yr.) | $3,726 | Live at Home | $7,452 |

| Public University, In State (4 yr.) | $9,716 | Live at Home | $38,864 |

| Public University, In State (4 yr.) | $19,716 | $78,864 | |

| Public University, Out of State (4 yr.) | $21,629 | $31,629 | $126,516 |

| Private College (4 yr.) | $35,676 | $45,676 | $182,704 |

You may need to adjust your college plan as circumstances change for you and in the job market. You can modify plans based on funding opportunities available to you (see next sections) and your location. You may prefer a community-college-only education, or you may complete two years at a community college and then transfer to a university to complete a bachelor’s degree. Living at home for the first two years or all of your college education will save a lot of money if your circumstances allow. Be creative!

Key to Success: Matching Student Debt to Postgraduation Income

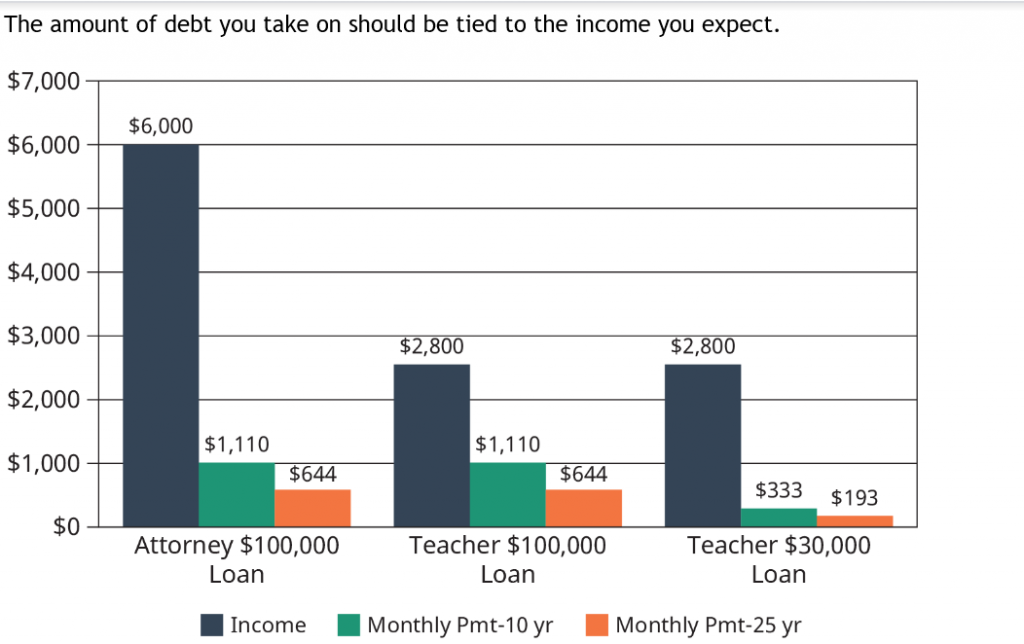

Students and parents often ask, “How much debt should I have?” The problem is that the correct answer depends on your personal situation. A big-firm attorney in a major city might make $120,000 in their first year as a lawyer. Having $100,00 or even $200,000 in student debt in this situation may be reasonable. But a high school teacher making $40,000 in their first year would never be able to pay off the debt.

Each field of employment brings with it an average income and assumed debt. This graph shows the impact of an attorney’s income versus debt, and then compares a teacher who took a $100,000 loan with one who took a $30,000 loan. Note the teacher’s income is the same in both cases. (Credit: Based on information from National Association of Colleges and Employers and US Bureau of Labor Statistics.)

Research Your Starting Salary

Begin by researching your expected starting salary when you graduate. Most students expect to make significantly more than they will actually make.17 As a result, your salary expectations are likely much higher than reality. Ask professors at your college what is typical for a recent graduate in your field, or do informational interviews with human resource managers at local companies. Explore the US Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Occupational Outlook Handbook. PayScale also has a handy tool for getting general information based on your personal experience and location. Search websites and talk to employees of companies that interest you for future employment to identify real starting salaries.

Undergraduate Degree: 1 x Annual Salary

For students working toward a bachelor’s or associate degree, both forms of undergraduate degrees, you should try to keep your student loans equal to or less than your expected first year’s salary. So if, based on research, you expect to make $40,000 in your first year out of college, then $33,000 in student loans would be a reasonable amount for you to pay out of a monthly budget with some sacrifice.

Advanced Degrees: 1–2 x Annual Salary

Once you’ve graduated with your bachelor’s degree, you may want to get an advanced degree such as a master’s degree, a law degree, a medical degree, or a doctorate. While these degrees can greatly increase your income, you still need to match your student debt to your expected income. Advanced degrees can often double your expected annual salary, meaning your total debt for all your degrees should be equal to or less than twice your expected first job income. A lower number for the debt portion of your education would be more manageable.

Your goal should be to pay for college using multiple methods so your student loan debt can be as small as possible, rather than just making low monthly payments on a large loan that will lead to a higher overall cost.

Types of Financial Aid: How to Pay for College

The true cost of college may be more than you expected, but you can make an effort to make the cost less than many might think. While the price tag for a school might say $40,000, the net cost of college may be significantly less. The net price for a college is the true cost a family will pay when grants, scholarships, and education tax benefits are factored in. The net cost for the average family at a public in-state school is only $3,980. And for a private school, free financial aid money reduces the cost to the average family from $32,410 per year to just $14,890.

If you haven’t visited your college’s financial aid office recently, it’s probably worth it to talk with them. You must seek out opportunities, complete paperwork, and learn and meet criteria, but it can save you thousands of dollars.

| Type of College | Average Published Yearly Tuition and Fees |

| Public Two-Year College (in-district students) | $3,440 |

| Public Four-Year College (in-state students) | $9,410 |

| Public Two-Year College (out-of-state students) | $23,890 |

| Private Four-Year College | $32,410 |

Grants and Scholarships

Grants and scholarships are free money you can use to pay for college. Unlike loans, you never have to pay back a grant or a scholarship. All you have to do is go to school. And you don’t have to be a straight-A student to get grants and scholarships. There is so much free money, in fact, that billions of dollars go unclaimed every year.18

While some grants and scholarships are based on a student’s academic record, many are given to average students based on their major, ethnic background, gender, religion, or other factors. There are likely dozens or hundreds of scholarships and grants available to you personally if you look for them.

Federal Grants

Federal Pell Grants are awarded to students based on financial need, although there is no income or wealth limit on the grant program. The Pell Grant can give you more than $6,000 per year in free money toward tuition, fees, and living expenses.19 If you qualify for a Pell Grant based on your financial need, you will automatically get the money.

Federal Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grants (FSEOGs) are additional free money available to students with financial need. Through the FSEOG program, you can receive up to an additional $4,000 in free money. These grants are distributed through your school’s financial aid department on a first-come, first-served basis, so pay close attention to deadlines.

Teacher Education Assistance for College and Higher Education (TEACH) Grants are designed to help students who plan to go into the teaching profession. You can receive up to $4,000 per year through the TEACH Grant. To be eligible for a TEACH Grant, you must take specific classes and majors and must hold a qualifying teaching job for at least four years after graduation. If you do not fulfill these obligations, your TEACH Grant will be converted to a loan, which you will have to pay back with both interest and back interest.

There are numerous other grants available through individual states, employers, colleges, and private organizations.

State Grants

Most states also have grant programs for their residents, often based on financial need. Eleven states have even implemented free college tuition programs for residents who plan to continue to live in the state. Even some medical schools are beginning to be tuition free. Check your school’s financial aid office and your state’s department of education for details.

College/University Grants and Scholarships

Most colleges and universities have their own scholarships and grants. These are distributed through a wide variety of sources, including the school’s financial aid office, the school’s endowment fund, individual departments, and clubs on campus.

Private Organization Grants and Scholarships

A wide variety of grants and scholarships and are awarded by foundations, civic groups, companies, religious groups, professional organizations, and charities. Most are small awards under $4,000, but multiple awards can add up to large amounts of money each year. Your financial aid office can help you find these opportunities.

Employer Grants and Scholarships

Many employers also offer free money to help employees go to school. A common work benefit is a tuition reimbursement program, where employers will pay students extra money to cover the cost of tuition once they’ve earned a passing grade in a college class. And some companies are going even further, offering to pay 100 percent of college costs for employees. Check to see whether your employer offers any kind of educational support.

Additional Federal Support

The federal government offers a handful of additional options for college students to find financial support.

Education Tax Credits

The IRS gives out free money to students and their parents through two tax credits, although you will have to choose between them. The American opportunity tax credit (AOTC) will refund up to $2,500 of qualifying education expenses per eligible student, while the lifetime learning credit (LLC) refunds up to $2,000 per year regardless of the number of qualifying students.

While the AOTC may be a better tax credit to choose for some, it can only be claimed for four years for each student, and it has other limitations. The LLC has fewer limitations, and there is no limit on the number of years you can claim it. Lifetime learners and nontraditional students may consider the LLC a better choice. Calculate the benefits for your situation.

The IRS warns taxpayers to be careful when claiming the credits. There are potential penalties for incorrectly claiming the credits, and you or your family should consult a tax professional or financial adviser when claiming these credits.

Federal Work-Study Program

The Federal Work-Study Program provides part-time jobs through colleges and universities to students who are enrolled in the school. The program offers students the opportunity to work in their field, for their school, or for a nonprofit or civic organization to help pay for the cost of college. If your school participates in the program, it will be offered through your school’s financial aid office.

Student Loans

Federal student loans are offered through the US Department of Education and are designed to give easy and inexpensive access to loans for school. You don’t have to make payments on the loans while you are in school, and the interest on the loans is tax deductible for most people. Direct Loans, also called Federal Stafford Loans, have a competitive fixed interest rate and don’t require a credit check or cosigner.

Direct Subsidized Loans

Direct Subsidized Loans are federal student loans on which the government pays the interest while you are in school. Direct Subsidized Loans are made based on financial need as calculated from the information you provide in your application. Qualifying students can get up to $3,500 in subsidized loans in their first year, $4,500 in their second year, and $5,500 in later years of their college education.

Direct Unsubsidized Loans

Direct Unsubsidized Loans are federal loans on which you are charged interest while you are in school. If you don’t make interest payments while in school, the interest will be added to the loan amount each year and will result in a larger student loan balance when you graduate. The amount you can borrow each year depends on numerous factors, with a maximum of $12,500 annually for undergraduates and $20,500 annually for professional or graduate students.

There are also aggregate loan limits that apply to put a maximum cap on the total amount you can borrow for student loans.

Direct PLUS Loans

Direct PLUS Loans are additional loans a parent, grandparent, or graduate student can take out to help pay for additional costs of college. PLUS loans require a credit check and have higher interest rates, but the interest is still tax deductible. The maximum PLUS loan you can receive is the remaining cost of attending the school.

Parents and other family members should be careful when taking out PLUS loans on behalf of a child. Whoever is on the loan is responsible for the loan forever, and the loan generally cannot be forgiven in bankruptcy. The government can also take Social Security benefits should the loan not be repaid.

Private Loans

Private loans are also available for students who need them from banks, credit unions, private investors, and even predatory lenders. But with all the other resources for paying for college, a private loan is generally unnecessary and unwise. Private loans will require a credit check and potentially a cosigner, they will likely have higher interest rates, and the interest is not tax deductible. As a general rule, you should be wary of private student loans or avoid them altogether.

Repayment Strategies

Payments on student loans will begin shortly after you graduate. While many websites, financial “gurus,” and talking heads in the media will encourage you to pay off your student loans as quickly as possible, you should give careful consideration to your repayment options and how they may impact your financial plans. Quickly paying off your student loans or refinancing your student loans into a private loan may be the worst option available to you.

Payment Plans

The federal government has eight separate loan repayment programs, each with their own way of calculating the payment you owe. Five of the programs tie loan payments to your income, which can make it easier to afford your student loans when you are just starting off in your career. The programs are described briefly below, but you should seek the help of a licensed fiduciary financial adviser familiar with student loans when making decisions related to student loan payment plans.

The standard repayment plan sets a consistent monthly payment to pay off your loan within 10 years (or up to 30 years for consolidated loans). You can also choose a graduated repayment plan, which will begin with lower payments and then increase the payment every two years. The graduated plan is also designed to pay off your student loans in 10 years (or up to 30 years for consolidated loans). A third option is the extended repayment plan, which provides a fixed or graduated payment for up to 25 years. However, none of these programs are ideal for individuals planning to seek loan forgiveness options, which are discussed below.

Beyond the “normal” repayment options, the government offers five income-based repayment options: (1) the Pay As You Earn (PAYE) repayment plan, (2) the Revised Pay As You Earn (REPAYE) repayment plan, (3) the Income-Based Repayment (IBR) plan, (4) the Income-Contingent Repayment (ICR) plan, and (5) the Income-Sensitive Repayment (ISR) plan. Each program has its method of calculating payments, along with specific requirements for eligibility and rules for staying eligible in the program. Many income-based repayment plans are also eligible for loan forgiveness after a set period of time, assuming you follow all the rules and remain eligible.

Loan Forgiveness Programs

Many income-based repayment options also have a loan forgiveness feature built into the repayment plan. If you make 100 percent of your payments on time and follow all the other plan rules, any remaining loan balance at the end of the plan repayment term (typically 20 to 30 years) will be forgiven. This means you will not have to pay the remainder on your student loans.

This loan forgiveness, however, comes with a catch: taxes. Any forgiven balance will be counted and taxed as income during that year. So if you have a $100,000 loan forgiven, you could be looking at an additional $20,000 tax bill that year (assuming you were in the 20 percent marginal tax rate).

Another option is the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program for students who go on to work for a nonprofit or government organization. If eligible, you can have your loans forgiven after working for 10 years in a qualifying public service job and making 120 on-time payments on your loans. A major advantage of PSLF is that the loan forgiveness may not be taxed as income in the year the loan is forgiven.

Consider Professional Advice

The complexity of the payment and forgiveness programs makes it difficult for non-experts to choose the best strategy to minimize costs. Additionally, the strict rules and potential tax implications create a minefield of potential financial problems. In 2017, the first year graduates were eligible for the PSLF program, 99 percent of applicants were denied due to misunderstanding the programs or having broken one of the many requirements for eligibility.20

Your Rights as a Loan Recipient

As a recipient of a federal student loan, you have the same rights and protections as you would for any other loan. This includes the right to know the terms and conditions for any loan before signing the paperwork. You also have the right to know information on your credit report and to dispute any loan or information on your credit file.

If you end up in collections, you also have several rights, even though you have missed loan payments. Debt collectors can only call you between 8 a.m. and 9 p.m. They also cannot harass you, threaten you, or call you at work once you’ve told them to stop. The United States doesn’t have debtors’ prisons, so anyone threatening you with arrest or jail time is automatically breaking the law.

Federal student loans also come with many other rights, including the right to put your loan in deferment or forbearance (pushing pause on making payments) under qualifying circumstances. Deferment or forbearance can be granted if you lose your job, go back to school, or have an economic hardship. If you have a life event that makes it difficult to make your payments, immediately contact the student loan servicing company on your loan statements to see if you can pause your student loan payments.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has created a series of sample letters you can use to respond to a debt collector. You can also file a complaint with the CFPB if you believe your rights have been violated.

Applying for Financial Aid, FAFSA, and Everything Else

Take this first step—you will need to do it. The federal government offers a standard form called the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), which qualifies you for federal financial aid and also opens the door for nearly all other financial aid. Most grants and scholarships require you to fill out the FAFSA, and they base their decisions on the information in the application.

The FAFSA only requests financial aid for the specific year you file your application. This means you will need to file a FAFSA for each year you are in college. Since your financial needs will change over time, you may qualify for financial aid even if you did not qualify before.

You can apply for the FAFSA through your college’s financial aid office or at studentaid.gov if you don’t have access to a financial aid office. Once you file a FAFSA, any college can gain access to the information (with your approval), so you can shop around for financial aid offers from colleges.

Maintaining Financial Aid

To maintain your financial aid throughout your college, you need to make sure you meet the eligibility requirements for each year you are in school, not just the year of your initial application. The basic requirements include being a US citizen or eligible non-citizen, having a valid Social Security number, and registering for selective service if required. Undocumented residents may receive financial aid as well and should check with their school’s financial aid office.

You also must make satisfactory academic progress, including meeting a minimum grade-point average, taking and completing a minimum number of classes, and making progress toward graduation or a certificate. Your school will have a policy for satisfactory academic progress, which you can get from the financial aid office.

What to Do with Extra Financial Aid Money

One expensive mistake that students make with financial aid money is spending the money on non-education expenses. Students often use financial aid, including student loans, to purchase clothing, take vacations, or dine out at restaurants. Nearly 3% spend student loan money on alcohol and drugs.21 While this seems like fun now, these non-education expenses are major contributors to student loan debt, which will make it harder for you to afford a home, take vacations, or save for your retirement after you graduate.

When you have extra student loan money, consider saving it for future education expenses. Just like you will need an emergency fund all your adult life, you will want an emergency fund for college when expensive books or travel abroad programs present unexpected costs. If you make it through your college years with extra money in your savings, you can use the money to help pay down debt.

Analysis Question

A closer look: How much student loan debt do you currently have, and how much do you think you’ll have by the end of college? How could this debt impact your future?

Working During College

Typical Student Jobs

College students can take on a range of jobs while in school, depending on their availability, experience, talents, and financial needs. For example, if a student is taking a lot of course credits in order to graduate early, he or she may not have time to work more than five hours a week. Let’s look at the types of jobs college students might have.

Work-Study Programs

Work study is part-time work that’s awarded to students as part of a financial aid package. Students can often find work study related to their areas of interest. For example, someone studying biology might have a work-study job taking inventory of lab supplies on campus. Because work-study jobs are a part of financial aid packages, students who simply want to earn extra money may not qualify.

Not all campus jobs are work-study related. Students may be able to ask their institution’s human resource director or individual campus departments to see if other work is available. For example, the office of the registrar might need help filing papers. It may also be possible to apply to become a resident adviser (RA) and get free room and board in exchange for living on campus and serving as a role model for students. Some students may prefer to seek work off-campus, instead, since they may be able to work more hours and avoid competing with other students for on-campus jobs.

Off-Campus Jobs

Students can certainly explore job opportunities in their communities. Such work might be related to a student’s field of interest—for example, a student interested in journalism might get a job writing ads for a local publication. Or it might be worth seeking a job that’s unrelated to school simply because it offers the most hours and pay. On the other hand, some may prefer on-campus jobs because their work supervisors are more respectful of their academic commitments and the need for flexible hours.

Internships

Similar to work-study opportunities, internships are usually related to a student’s area of interest. For example, a marketing student may get an internship working with a marketing director and contributing to the company’s social media campaigns. While internships can provide invaluable work experience, it can be hard to find ones that are paid.

Summer Jobs

Students who are concerned about not having enough time to work during college may wait and find part-time or full-time work during summer break. Such opportunities can be found through one’s guidance counselor, financial aid department, community members, or even online. One disadvantage of summer jobs is that they don’t last very long—the work is typically seasonal.

Working During College

Finding a job as a college student can be both exciting and stressful, and it’s not for everyone. For example, students who have already received tuition assistance through scholarships and have full course loads may not have enough time for work. Let’s look more closely at the advantages and disadvantages of working during college:

Pros

- Earning extra money: One of the most obvious benefits to working during college is earning extra money for college expenses.

- Enhanced budgeting skills: Students with the responsibility of working may learn to budget their money better since they have to earn it themselves.

- Enhanced time-management skills: Students who have to juggle classes, work, and possibly other activities such as clubs or sports may actually excel in classes because they learn how to effectively management their time.

- Networking: Students may not only get work experience in a field related to their interests, but they may also meet people who can help them later when they’re ready for a career. For example, a law student who gets a job as a file clerk with a law firm may be able to ask the lawyers at the firm for recommendations when she applies to law school.

Cons

- Lack of time-management skills: Though working during college can help students build time-management skills, those who aren’t used to balancing activities may struggle. For example, a student who heads to college straight from high school without any prior job experience (or with few extracurricular activities during high school) may have trouble meeting multiple academic and job obligations and commitments.

- Lack of free time: If students take on a lot of work hours while in college, they may not have time for other activities or opportunities, such as joining clubs related to their interests or finding volunteer work or internships that might help them discover career opportunities and connections. These “extras” are actually significant résumé items that can make students more employable after college.

Deciding whether or not to work while you’re in college is obviously personal decision that involves your own comfort level and situation. Some students may prefer to put off looking for a job until after the first semester of college, so they can better gauge their work load and schedule, while others may prefer to avoid working altogether. For some, the question isn’t “Should I or shouldn’t I get a job?” but “How much should I work?” In other words, the challenge is to strike the right balance between schoolwork, social activities, and earning money.

Employment Resources

We’ve identified some categories of work that are typically available to college students, but what about the actual process of finding a suitable job? You have a number of employment resources available to you on campus, online, and in the community:

- Career centers: Most colleges have a career center where you can learn about job opportunities both on and off campus and also during the summer. Career center also have staff who can help you practice the interview process and write effective resumes and cover letters.

- Career fairs: Many colleges organize on-campus career fairs (like the one shown in the photo, below). Local—and, in some cases, national—companies are invited to set up booths and share information with you about potential job and career opportunities.

- Online job search: Web sites such as Careerbuilder, Snagajob, and even Craigslist post job listings for positions ranging from seasonal retail work to freelance writing opportunities. You should look for listings that include company and contact information, so you can confirm that the leads are legitimate and reputable.

- Community businesses and places of worship: You may be surprised by the job opportunities they can find right in their own backyard. Don’t overlook community centers or bulletin boards in places like neighborhood coffee shops and grocery stores—someone always seems to need a dog walker, house sitter, or nanny. Churches, temples, and mosques are additional places that often have notice boards with “Help Wanted” listings.

Personal Financial Planning

If you fail to plan, you are planning to fail.

Honestly, practicing money management isn’t that hard to figure out. In many ways it’s similar to playing a video game. The first time you play a game, you may feel awkward or have the lowest score. Playing for a while can make you OK at the game. But if you learn the rules of the game, figure out how to best use each tool in the game, read strategy guides from experts, and practice, you can get really good at it.

Money management is the same. It’s not enough to “figure it out as you go.” If you want to get good at managing your money, you must treat money like you treat your favorite game. You have to come at it with a well-researched plan. Research has shown that people with stronger finances are healthier1 and happier,2 have better marriages,3 and even have better cognitive functioning.4

What Students Say

- What is your top immediate financial priority?

- Minimizing debt

- Get a better job

- Pay for college

- Move out on my own

- Get a car

- Increase my savings or money on hand

- Which aspect of your finances concerns you the most?

- The amount of debt I have or will have

- Getting a job that will pay well enough

- Being financially independent

- Supporting my family

- Planning/saving for the future

- When considering how to pay for college, which of the following do you know least about?

- Grants

- Scholarships

- Loans

- Work-study programs

You can also take the anonymous What Students Say surveys to add your voice to this textbook. Your responses will be included in updates.

You can also take the anonymous What Students Say surveys to add your voice to this textbook. Your responses will be included in updates.

Students offered their views on these questions, and the results are displayed in the graphs below.

What is your top immediate financial priority?

Which aspect of your finances concerns you the most?

When considering how to pay for college, which of the following do you know least about?

Financial Planning Process

Personal goals and behaviors have a financial component or consequence. To make the most of your financial resources, you need to do some financial planning. The financial planning process consists of five distinct steps: goal setting, evaluating, planning, implementing, and monitoring. You can read in more depth about SMART goals in chapter three.

Financial Planning in Five Steps

- Develop Personal Goals

- What do I want my life to look like?

- Identify and Evaluate Alternatives for Achieving Goals for My Situation

- What do my savings, debt, income, and expenses look like?

- What creative ways are available to get the life I want?

- Write My Financial Plan

- What small steps can I take to start working toward my goals?

- Implement the Plan

- Begin taking those steps, even if I can only do a few small things each week.

- Monitor and Adjust the Plan

- Make sure I don’t get distracted by life. Keep taking those small steps each week. Make adjustments when needed.

Figure 10.5 Steps of financial planning.

How to Use Financial Planning in Everyday Life

The financial planning process isn’t only about creating one big financial plan. You can also use it to get a better deal when you buy a car or computer or rent an apartment. In fact, anytime you are thinking about spending a lot of money, you can use the financial planning process to pay less and get more.

To explore financial planning in depth, we’ll use the example of buying a car.

1. Develop Goals

First, what do you really need? If you’re looking for a car, you probably need transportation. Before you decide to buy a car, consider alternatives to buying a car. Could you take a bus, walk, or bike instead? Often one goal can impact another goal. Cars are typically not good financial investments. We have cars for convenience and necessity, to earn an income and to enjoy life. Financially, they are an expense. They lose value, or depreciate, rather than increasing in value, like savings. So buying a car may slow your savings or retirement plan goals. Cars continually use up cash for gas, repairs, taxes, parking, and so on. Keep this in mind throughout the planning process.

2. Identify and Evaluate Alternatives for Achieving Goals in Your Current Situation.

For this example, let’s assume that you have determined the best alternative is to buy a car. Do you need a new car? Will your current car last with some upkeep? Consider a used car over a new one. On average, a new car will lose one-fifth of its value during its first year.5 Buying a one-year-old car is like getting a practically new car for a 20 percent discount. So in many cases, the best deal may be to buy a five- or six-year-old car. Sites such as the Kelley Blue Book website (KBB.com) and Edmunds.com can show you depreciation tables for the cars you are considering. Perhaps someone in your family has a car they will sell you at a discount.

Do you know how much it will cost in total to own the car? It will help to check out the total cost of ownership tools (also on KBB.com and Edmunds.com) to estimate how much each car will cost you in maintenance, repairs, gas, and insurance. A cheap car that gets poor gas mileage and breaks down all the time will actually cost you more in the long run.

3. Write Down Your Financial Plan

| Goal | Item | Details | Budget | Timeline |

| Transportation/Car | 2014 Toyota Camry | Black, A/C, power windows, less than 60,000 miles | Car $12,000 (max)

Down payment $3,000 Insurance $100/mo Sales tax $900 + Licensing $145 Cash needed $4,145 |

Have $3600 in savings for this.

Save $50/week. Purchase in approximately 11 weeks. |

| Computer | Used or refurbished laptop | Dell w/ Windows, minimum 13″, 128G hard drive, HD Graphics | $300

Use free Windows update from school. Use free Wi-Fi at school. |

Sell current laptop for $100.

Buy refurbished from Dell site for $289. $189 on credit card. Pay off when statement comes. |

4. Implement Your Plan

Once you’ve narrowed down which car you are looking for, do more online research with resources such as Kelley Blue Book to see what is for sale in your area. You can also begin contacting dealerships and asking them if they have the car you are looking for with the features you want. Ask the dealerships with the car you want to give you their best offer, then compare their price to your researched price. You may have to spend more time looking at other dealerships to compare offers, but one goal of online research is to save time and avoid driving from place to place if possible.

When you do go to buy the car, bring a copy of your written plan into the dealership and stick to it. If a dealership tries to switch you to a more expensive option, just say no, or you can leave to go to another dealership. Remember Elan in our opening scenario? He went shopping alone and caved to the pressure and persuasion of the salesperson. If you feel it is helpful, take a responsible friend or family member with you for support.

5. Monitor and Adjust the Plan to Changing Circumstances and New Life Goals

Life changes, and things wear out. Keep up the recommended maintenance on the car (or any other purchase). Keep saving money for your emergency fund, then for your next car. The worst time to buy a car is when your current car breaks down, because you are easier to take advantage of when you are desperate. When your car starts giving you trouble or your life circumstances start to change, you will be ready to shop smart again.

A good practice is to keep making car payments once the car loan is paid off. If you are paying $300 per month for a car loan, when the loan is paid off, put $300 per month into a savings account for a new car instead. Do it long enough and you can buy your next car using your own money!

Use the Financial Planning Process for Everything

The same process can be used to make every major purchase in your life. When you rent an apartment, begin with the same assessment of your current financial situation, what you need in an apartment, and what goals it will impact or fulfill. Then look for an apartment using a written plan to avoid being sold on a more expensive place than you want.

You can even use the process of assessing and planning for small things such as buying textbooks or weekly groceries. While saving a few bucks each week may seem like a small deal, you will gain practice using the financial planning process, so it will become automatic for when you make the big decisions in life. Stick to your plan.

Savings, Expenses, and Budgeting

“Do not save what is left after spending; instead spend what is left after saving.”

—Warren Buffett6

What is the best way to get to the Mississippi River from here? Do you know? To answer the question, even with a map app, you would need to know where you are starting from and exactly where on the river you want to arrive before you can map the best route. Our financial lives need maps, too. You need to know where you are now and where you want to end up in order to map a course to meet the goal.

You map your financial path using a spending and savings plan, or budget, which tracks your income, savings, and spending. You check on your progress using a balance sheet that lists your assets, or what you own, and your liabilities, or what you owe. A balance sheet is like a snapshot, a moment in time, that we use to check our progress.

Budgets

The term budget is unpleasant to some people because it just looks like work. But who will care more about your money than you? We all want to know if we have enough money to pay our bills, travel, get an education, buy a car, etc. Technically, a budget is a specific financial plan for a specified time. Budgets have three elements: income, saving and investing, and expenses.

Income

Income most often comes from our jobs in the form of a paper or electronic paycheck. When listing your income for your monthly budget, you should use your net pay, also called your disposable income. It is the only money you can use to pay bills. If you currently have a job, look at the pay stub or statement. You will find gross pay, then some money deducted for a variety of taxes, leaving a smaller amount—your net pay. Sometimes you have the opportunity to have some other, optional deductions taken from your paycheck before you get your net pay. Examples of optional deductions include 401(k) or health insurance payments. You can change these amounts, but you should still use your net pay when considering your budget.

Some individuals receive disability income, social security income, investment income, alimony, child support, and other forms of payment on a regular basis. All of these go under income. During school, you may receive support from family that could be considered income. You may also receive scholarships, grants, or student loan money.

Saving and Investing

The first bill you should pay is to yourself. You owe yourself today and tomorrow. That means you should set aside a certain amount of money for savings and investments, before paying bills and making discretionary, or optional, purchases. Savings can be for an emergency fund or for short-term goals such as education, a wedding, travel, or a car. Investing, such as putting your money into stocks, bonds, or real estate, offers higher returns at a higher risk than money saved in a bank. Investments include retirement accounts that can be automatically funded with money deducted from your paycheck. Automatic payroll deductions are an effective way to save money before you can get your hands on it. Setting saving as a priority assures that you will work to make the payment to yourself as hard as you work to make your car or housing payment. The money you “pay” toward saving or investing will earn you back your money, plus some money earned on your money. Compare this to the cost of buying an item on credit and paying your money plus interest to a creditor. Paying yourself first is a habit that pays off!

Pay yourself first! Put something in savings from every paycheck or gift.

Expenses

Expenses are categorized in two ways. One method separates them into fixed expenses and variable expenses. Rent, insurance costs, and utilities (power, water) are fixed: they cost about the same every month and are predictable based on your arrangement with the provider. Variable expenses, on the other hand, change based on your priorities and available funds; they include groceries, restaurants, cell phone plans, gas, clothing, and so on. You have a good degree of control over your variable expenses. You can begin organizing your expenses by categorizing each one as either fixed or variable.

A second way to categorize expenses is to identify them as either needs or wants. Your needs come first: food, basic clothing, safe housing, medical care, and water. Your wants come afterward, if you can afford them while sticking to a savings plan. Wants may include meals at a restaurant, designer clothes, video games, other forms of entertainment, or a new car. After you identify an item as a need or want, you must exercise self-control to avoid caving to your desire for too many wants.

Activity

List the last ten purchases you made, and place each of them in the category you think is correct.

| Item | Need Expense $ | Want Expense $ |

| Totals |

How do your total “need” expenses compare to your total “want” expenses? Should either of them change?

Budgets are done in a chart or spreadsheet format and often look like the ones below. Pay attention to how the first budget differs from the second.

| Income (use net monthly pay) | |

| Paycheck | $2200 |

| Other | $300 |

| Total Income | $2500 |

| Saving and Investing | |

| Savings Account | $120 |

| Investments | $240 |

| Amount Left for Expenses | $2140 |

| Expenses (Monthly) | |

| Housing | $750 |

| Car Payment/Insurance | $450 |

| Groceries | $400 |

| Restaurants/Food Delivery | $100 |

| Internet | $60 |

| Phone | $60 |

| Medical Insurance and Co-pays | $120 |

| Gas | $200 |

| Total Expenses | $2140 |

| Balance (Amount left for expenses minus total expenses) | $0 |

This budget balances because all money is accounted for.

| Income (use net monthly pay) | |

| Paycheck | $2200 |

| Other | $300 |

| Total Income | $2500 |

| Saving and Investing | |

| Savings Account | $120 |

| Investments | $240 |

| Amount Left for Expenses | $2140 |

| Expenses (Monthly) | |

| Housing | $750 |

| Car Payment/Insurance | $450 |

| Groceries | $400 |

| Restaurants/Food Delivery | $225 |

| Internet | $60 |

| Phone | $75 |

| Medical Insurance and Co-pays | $120 |

| Gas | $250 |

| Total Expenses | $2330 |

| Balance (Amount left for expenses minus total expenses) | -$190 |

The table notes that Restaurants, Phone, and Gas are more expensive in this budget, so the total expenses are more than the amount left for them.

Balancing Your Budget

Would you take all your cash outside and throw it up in the air on a windy day? Probably not. We want to hold on to every cent and decide where we want it to go. Our budget allows us to find a place for each dollar. We should not regularly have money left over. If we do, we should consider increasing our saving and investing. We also should not have a negative balance, meaning we don’t have enough to pay our bills. If we are short of money, we can look at all three categories of our budget: income, savings, and expenses.

We could increase our income by taking a second job or working overtime, although this is rarely advisable alongside college coursework. The time commitment quickly becomes overwhelming. Another option is to cut savings, or there’s always the possibility of reducing expenses. Any of these options in combination can work.

Another, even less desirable option is to take on debt to make up the shortfall. This is usually only a short-term solution that makes future months and cash shortages worse as we pay off the debt. When we budget for each successive month, we can look at what we actually spent the month before and make adjustments.

Tracking the Big Picture

When you think about becoming more financially secure, you’re usually considering your net worth, or the total measure of your wealth. Earnings, savings, and investments build up your assets—that is, the valuable things you own. Borrowed money, or debt, increases your liabilities, or what you owe. If you subtract what you owe from what you own, the result is your net worth. Your goal is to own more than you owe.

When people first get out of college and have student debt, they often owe more than they own. But over time and with good financial strategies, they can reverse that situation. You can track information about your assets, liabilities, and net worth on a balance sheet or part of a personal financial statement. This information will be required to get a home loan or other types of loans. For your net worth to grow in a positive direction, you must increase your assets and decrease your liabilities over time.

Assets (Owned) – Liabilities (Owed) = Net Worth

Analysis Question

Can you identify areas in your life where you are losing money by paying fees on your checking account or interest on your loans? What actions could you take to stop giving away money and instead set yourself up to start earning money?

| Good Practices That Build Wealth | Bad Practices That Dig a Debt Hole |

| Tracking all spending and saving | Living paycheck to paycheck with no plan |

| Knowing the difference between needs and wants | Spending money on wants instead of saving |

| Resisting impulse buying and emotional spending | Using credit to buy more that you need and increasing what you owe |

Get Connected

You can write down your budget on paper or using a computer spreadsheet program such as Excel, or you can find popular budgeting apps that work for you.7 Some apps link to your accounts and offer other services such as tracking credit cards and your credit score. The key is to find an app that does what you need and use it.

Here are some examples:

Credit Cards and Other Debt

The Danger of Debt

When you take out a loan, you take on an obligation to pay the money back, with interest, through a monthly payment. You will take this debt with you when you apply for auto loans or home loans, when you enter into a marriage, and so on. Effectively, you have committed your future income to the loan. While this can be a good idea with student loans, take on too many loans and your future self will be poor, no matter how much money you make. Worse, you’ll be transferring more and more of your money to the bank through interest payments.

Compounding Interest

While compounding works to make you money when you are earning interest on savings or investments, it works against you when you are paying the interest on loans. To avoid compounding interest on loans, make sure your payments are at least enough to cover the interest charged each month. The good news is that the interest you are charged will be listed each month on the loan account statements you are sent by the bank or credit union, and fully amortized loans will always cover the interest costs plus enough principal to pay off what you owe by the end of the loan term.

The two most common loans on which people get stuck paying compounding interest are credit cards and student loans. Paying the minimum payment each month on a credit card will just barely cover the interest charged that month, while anything you buy with the credit card will begin to accrue interest on the day you make the purchase. Since credit cards charge interest daily, you’ll begin paying interest on the interest immediately, starting the compound interest snowball working against you. When you get a credit card, always pay the credit card balance down to $0 each month to avoid the compound interest trap.

Student loans are another way you can be caught in the compound interest trap. When you have an unsubsidized student loan or put your loans into deferment, the interest continues to rack up on the loans. Again, you’ll be charged interest on the interest, not just on the original loan amount, forcing you to pay compound interest on the loan.

Sacrificing Your Future Fun

When you graduate college, you are most likely to graduate with student loan debt and credit card debt.11 Many students use credit cards and student loans to allow them to pay for fun today, such as trips, clothing, and expensive meals.

Getting into debt while in college forces you to sacrifice your future fun. Say you take out $100,000 in student loans instead of the $50,000 you need, doubling your monthly payment. You are not just making an extra $338 payment; you are also sacrificing anything else you can do with that money. You sacrifice that extra $338 a month, every month, for the next twenty-five years. You can’t use it to go to the movies, pay down other debt, save for a home, take a vacation, or throw a party. When you sign those papers, you sacrifice all those opportunities every month for decades. As a result, when you take out a loan, you should make sure it’s a good loan.

How Much Good Debt to Take On

A drink of water is refreshing on a hot day and is required to stay alive. Too much water, however, and you will drown.

During college and for the first few years after graduation, most students should only have two loans: student loans and possibly a car loan. We’ve already discussed your student loans, which should be equal to or less than your first year’s expected salary after graduation.

When you get a car, you should keep your car payment to between 10 and 20 percent of your monthly take-home pay. This means if your paycheck is $200 per week, your car payment should be no more than $80–$160 each month.

In total, you want your debt payments (plus rent if you are renting) to be no more than 44 percent of your take-home pay. If you are planning to build wealth, however, you want to cap it at 30 percent of take-home pay.

Signs You Have Too Much Debt

You can consider yourself in too much debt if you have any of the following situations:

- You cannot make your minimum credit card payments.

- Your money is gone before your next paycheck.

- Bill collectors are contacting you.

- You are unable to get a loan.

- Your paycheck is being garnished by creditor.

- You are considering a debt consolidation loan with extra fees added.

- Your items are repossessed.

- You do not know your debt or financial situation.

Getting and Using a Credit Card

One of the most controversial aspects of personal finance is the use of credit cards. While credit cards can be an incredibly useful tool, their high interest rates, combined with the how easily credit cards can bury you in debt, make them extremely dangerous if not managed correctly.

Reflect on Elan from the chapter introduction and how he felt. How would you (or did you) feel to hold a new credit card with a $2,000 spending limit?

Benefits of a Credit Card

There are three main benefits of getting a credit card. The first is that credit cards offer a secure and convenient method of making purchases, similar to using a debit card. When you carry cash, you have the potential of having the money lost or stolen. A credit card or debit card, on the other hand, can be canceled and replaced at no cost to you.

Additionally, credit cards offer greater consumer protections than debit cards do. These consumer protections are written into law, and with credit cards you have a maximum liability of $50. With a debit card, you are responsible for transfers made up until the point you report the card stolen. In order to have the same protections as with credit cards, you need to report the card lost or stolen within 48 hours. The longer you wait to report the loss of the card, or the longer it takes you to realize you lost your card, the more money you may be responsible for, up to an unlimited amount.12

The final benefit is that a credit card will allow you to build your credit score, which is helpful in many aspects of life. While most people associate a credit score with getting better rates on loans, credit scores are also important to getting a job, lowering car insurance rates, and finding an apartment.13

What Is a Good Credit Score?

Most credit scores have a 300–850 score range. The higher the score, the lower the risk to lenders. A “good” credit score is considered to be in the 670–739 score range.

| Credit Score Ranges | Rating | Description |

| < 580 | Poor | This credit score is well below the average score of US consumers and demonstrates to lenders that the borrower may be a risk. |

| 580-669 | Fair | This credit score is below the average score of US consumers, though many lenders will approve loans with this score. |

| 670-739 | Good | This credit score is near or slightly above the average of US consumers, and most lenders consider this a good score. |

| 740-799 | Very Good | This credit score is above the average of US consumers and demonstrates to lenders that the borrower is very dependable. |

| 800+ | Exceptional | This credit score is well above the average score of US consumers and clearly demonstrates to lenders that the borrower is an exceptionally low risk. |

Components of a Credit Score and How to Improve Your Credit

Credit scores contain a total of five components. These components are credit payment history (35 percent), credit utilization (30 percent), length of credit history (15 percent), new credit (10 percent), and credit mix (10 percent). The main action you can take to improve your credit score is to stop charging and pay all bills on time. Even if you cannot pay the full amount of the credit card balance, which is the best practice, pay the minimum on time. Paying more is better for your debt load but does not improve your score. Carrying a balance on a credit card does not improve your score. Your score will go down if you pay bills late and owe more than 30 percent of your credit available. Your credit score is a reflection of your willingness and ability to do what you say you will do—pay your debts on time.

How to Use a Credit Card

All the benefits of credit cards are destroyed if you carry credit card debt. Credit cards should be used as a method of paying for things you can afford, meaning you should only use a credit card if the money is already sitting in your bank account and is budgeted for the item you are buying. If you use credit cards as a loan, you are losing the game.

Every month, you should pay your credit card off in full, meaning you will be bringing the loan amount down to $0. If your statement says you charged $432.56 that month, make sure you can pay off all $432.56. If you do this, you won’t pay any interest on the credit card.

But what happens if you don’t pay it off in full? If you are even one cent short on the payment, meaning you pay $432.55 instead, you must pay daily interest on the entire amount from the date you made the purchases. Your credit card company, of course, will be perfectly happy for you to make smaller payments—that’s how they make money. It is not uncommon for people to pay twice as much as the amount purchased and take years to pay off a credit card when they only pay the minimum payment each month.

What to Look for in Your Initial Credit Card

- Find a Low-Rate Credit Card: Even though you plan to never pay interest, mistakes will happen, and you don’t want to be paying high interest while you fix a misstep. Start by narrowing the hundreds of card options to the few with the lowest APR (annual percentage rate).

- Avoid Cards with Annual Fees or Minimum Usage Requirements: Your first credit card should ideally be one you can keep forever, but that’s expensive to do if they charge you an annual fee or have other requirements just for having the card. There are many options that won’t require you to spend a minimum amount each month and won’t charge you an annual fee.

- Keep the Credit Limit Equal to Two Weeks’ Take-Home Pay: Even though you want to pay your credit card off in full, most people will max out their credit cards once or twice while they are building their good financial habits. If this happens to you, having a small credit limit makes that mistake a small mistake instead of a $5,000 mistake.

Avoid Rewards Cards

Everyone loves to talk about rewards cards, but credit card companies wouldn’t offer rewards if they didn’t earn them a profit. Rewards systems with credit cards are designed by experts to get you to spend more money and pay more interest than you otherwise would. Until you build a strong habit of paying off your card in full each month, don’t step into their trap.

Assignment: Working Objective

- Identify jobs that college students frequently hold

- Assess what type of job might best fit your current needs and situation

Directions

- Schedule a brief interview with a college representative from an institution who works with students to help them find jobs. This representative might be from the career center, counseling services, or the human resource department.

- Considering your field(s) of interest, personal skills, and lifestyle, ask the college representative the following questions:

- What types of jobs would you recommend based on my interests and skills as me? Why?

- What types of jobs would be most compatible with my availability/schedule?

- What are the pros and cons of these jobs?

- After the interview, write a short paper (1–2 pages) summarizing what you found out. Do any of the jobs the college representative mentioned sound like opportunities you might pursue? Why or why not?